Garden Allies: Amphibians

Contributor

I was given a toad, once, and released it into a small lath house we called our jungle room. At times, swinging gently in the hammock, listening to the mesmerizing sounds of a Tropical Rainforest CD, I would see Toad emerge from his home. It was my belief that Toad was drawn out by the recorded deluge. Toads, it turns out, can live for many years in one place, and my family was sad when Toad finally disappeared from our lives. It has been many years since I thought of our warty pet, until last summer, when I witnessed a toad emergence in the Central Valley. As I stepped gingerly among the dime-sized toadlets, I was sorely tempted to scoop one up (or maybe three or thirty!), and bring them home. The tiny toads were (sorry, words fail me here) simply adorable! Their threatened status stayed my hand; while I still long for a garden toad, I hope that the habitat I am creating may eventually lure them into my garden.

An easier task is to introduce Pacific chorus frogs to the garden. No longer known as Pacific tree frog, since it spends little time in trees, this diminutive frog is renowned for—you guessed it—singing. A nearby pond is a favorite haunt of the cheery little frogs with the distinctive eye stripe and large toe pads. As I approach, however quietly, the raucous chorus ends, until I step silently into the shade of an oak. Soon, one voice braves the silence, then several companions join in, until finally the full cacophony resumes. Unfortunately, our old cast-iron tub, sunk into a corner of our garden and serving as a home to dragonfly larvae and other assorted aquatic insects, does not harbor this delightful little frog. In such a small environment, the voracious predatory dragonfly larvae relentlessly hunt down the tadpoles. Unless it is a large, well-vegetated pond, a successful frog pond must be emptied annually to eliminate such predatory species. So, why not have two ponds? We are installing a second tub designated for frogs, equipped with plants and plenty of spots to easily get in and out of the water.

Keep an eye (and ear) alert to the presence of the invasive, exotic bullfrog, which can quickly decimate native frogs, such as the now-threatened red-legged and yellow-legged species, and is known to eat baby western pond turtles, contributing to their alarming decline. Bullfrogs are also known to eat snakes and even ducklings. An occasional water change will control bullfrogs, whose larvae may require a full year to develop.

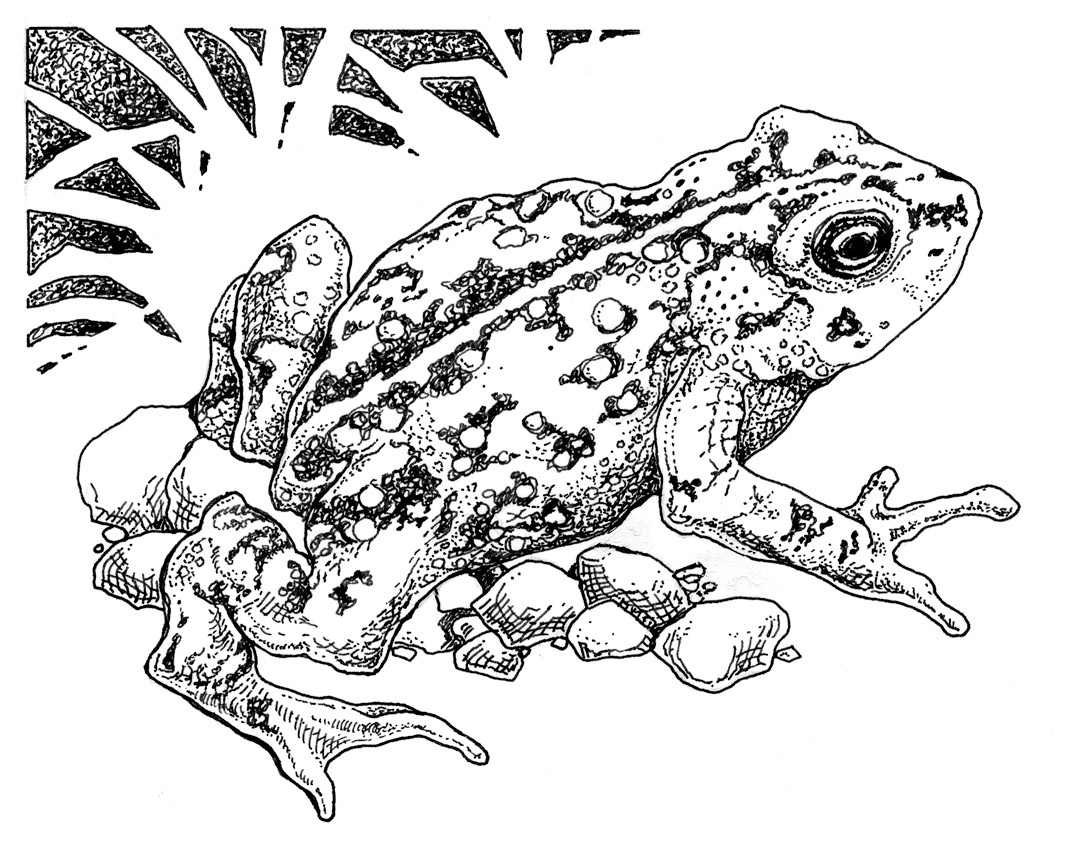

Frogs, toads, and salamanders are not the first creatures that might come to mind when thinking about garden allies. Frogs and toads are easily distinguished by their gait: while frogs hop, toads generally walk. Toads also are equipped with poison glands that secrete toxins as protection against predators. Salamanders are recognized by their elongated body—lizard-shaped, but free of scales. Yet one useful characteristic unites them all: they eat heaps of insects and other invertebrates! Although they are generalist predators, indiscriminately eating the good guys along with the bad, they are a fascinating part of a garden environment.

Pacific chorus frogs will make their home almost anywhere that water can be found; even in urban areas, gardeners with woodsy gardens may be pleasantly surprised to find the delicate slender salamander residing under a pot or rotting branch. A friend tells me that she was sitting on her patio one evening, in a residential neighborhood, when she was surprised to spot a Pacific giant salamander appear from behind a pot. The Laguna de Santa Rosa, Sebastopol’s big backyard wetland a half-mile distant, was the probable source of the welcome visitor. Among the largest land salamanders in the world, this formidable salamander may reach twelve inches. If handled roughly, it may bark or snarl, and can deliver a painful bite!

As tempting as it may be, gardeners should refrain from catching wild amphibians to bring home. Many species are threatened, and there are regulations on the capture and transportation of most species. Raising tadpoles, a miracle in any child’s life, requires a bit more investigation than it once did, but is still a worthwhile endeavor. The best resource may be another gardener’s backyard pond, but why not install your own frog pond, and simply wait for their inevitable arrival?

An appreciation of the frog’s watery life cycle may help our future citizens turn their attention to the importance of wetland preservation. Frogs, toads, and their relatives are threatened in the wild for many reasons. Loss of habitat is perhaps the biggest factor in the reduction of amphibian populations, especially since many species migrate between aquatic habitats during breeding season. With their moist, absorbent skin, amphibians serve as a biological indicator of environmental changes, often reacting to increases in pollution and UV radiation by exhibiting distressing mutations. Many species appear to be particularly sensitive to climate change, and often cannot survive even small changes in temperature. The problem of invasive species is not limited to the now ubiquitous bullfrog, but includes other species of amphibians, fish, and crayfish. If that were not enough, we now know that a fungus (chytrid), which attacks delicate amphibian skin, is the culprit in some regional extinctions. Good reasons, all, to create amphibian-friendly habitats in our gardens.

In a Nutshell

Popular Names:

Frogs, toads, salamanders, newts.

Scientific Name:

Class: Amphibia. Major groups found in gardens include frogs and toads (Order: Anura), and salamanders (Order: Caudata).

Common Garden Species:

Pacific chorus frog or Pacific tree frog (Hyla regilla, syn. Pseudacris regilla, and related species), western toad (Bufo boreas and subspecies), and the exotic bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana). Occasionally in gardens: Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus) and slender salamander (Batrachoseps species).

Distribution:

Throughout the West Coast, over thirty-five species of frogs and toads, and over forty species of salamanders.

Life Cycle:

Most amphibians undergo complete metamorphosis, transforming from an aquatic larva (tadpole) to a terrestrial adult. Jelly-coated eggs are laid in water in bundles or strands. Some salamanders lay eggs in moist garden soils; eggs hatch into small but fully formed adults. Some amphibians remain in a larval stage as adults, a condition called neoteny; Pacific giant salamanders are frequently neotenous.

Appearance:

Amphibians have four legs and glandular, moist skin with no scales, feathers, or hair. Coloring is varied, sometimes even within a species; Pacific chorus frog coloration ranges from bright green to shades of brown.

Life Span:

Little is known of many amphibian life spans, especially as adults. The western toad, once mature, is thought to live up to twelve years. Many amphibians’ larval stage takes place in ephemeral bodies of water.

Diet:

Insects, slugs, earthworms, sowbugs, and other invertebrates, depending upon species. Bullfrogs are known to eat snakes, ducklings, and other birds. Pacific giant salamanders may eat rodents and other salamanders.

Favorite plants:

Plants that grow in the moist situations amphibians favor. Pond-edge plants and aquatic plants that provide cover to protect vulnerable tadpoles from predators.

Benefits:

Melodies in the garden! Many amphibians eat invertebrate pests.

Problems:

Invasive bullfrogs should be eliminated from backyard ponds.

Interesting facts:

The sticky feet of Pacific chorus frogs are of interest to scientists looking for ways to improve traction on car tires. Native Americans believe that there is an individual tree frog in existence for each person. Zot is the special term for the quick flick of a frog’s tongue when it captures its prey.

Sources:

Check regulations on the capture and movement of amphibians; many species are protected.

More information:

Robert C Stebbins’s Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians is unparalleled. As both author and illustrator, Stebbins’s more compact California Amphibians and Reptiles should suffice in California. A great site for anyone in the Pacific Coast region is www.californiaherps.com, not only to listen to the numerous recordings of frog and toad songs, but for the wonderful photographs of amphibians and their typical habitat, and for links to other useful sites such as https://www.pnwhs.org/. Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast, on tape or CD, is available from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Responses