Garden Allies: Butterflies

Contributor

For children living in a tropical wonderland spotting yet another example of the extraordinary variety of life seems almost commonplace, or at least not unexpected. Yet, even as a child living in Singapore, I instantly knew that to see Rajah Brooke’s Birdwing (Trogonoptera brookiana) in its natural habitat, in the Cameron Highlands in Malaysia, was a memory to be treasured forever. Butterflies are well-loved even by gardeners who profess profound dislike for other insects. Mythologies and folk stories, art, music, and literature are all rich with butterfly imagery.

Butterfly gardens filled with nectar-rich flowering plants are popular in public and private landscapes. However, asking where the caterpillar garden is located is likely to be met with disbelief. The vision of tattered foliage draped on bare branches gives pause to many a well-meaning butterfly gardener facing the prospect of providing sustenance for these voracious leaf-eating insects. Yet without caterpillars, there would be no butterflies. [sidebar] The obligate ecological relationship between certain caterpillars and their associated larval host plants was the foundation for a seminal 1964 scientific paper on evolution. Authors Paul Ehrlich and Peter Raven documented the association of certain butterfly and plant species, and related it to the toxic secondary compounds produced by plants. They popularized a now familiar word, ‘coevolution’, defined by scientists as “a reciprocal evolutionary change in two interacting species,” and proposed that plant diversity was inextricably linked to lepidopteran diversity. [/sidebar]

With careful planning, a caterpillar garden habitat can be pleasing; many host plants suffer little damage, while others can be planted in an inconspicuous corner where they will blend into the background. Caterpillar garden design is facilitated by caterpillars’ generally finicky nature. Most caterpillars prefer to feed on a narrow range of [glossary term=host plant/larval host” content “host plant”] species, starving to death rather than accepting a substitute.

Monarch caterpillars (Danaus plexippus) feed only on milkweed (Asclepias spp.) and a few closely related plant species, and Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor) caterpillars dine on Dutchman’s pipe (Aristolochia). Fritillary species may use members of the violet and passion vine families as [glossary term=”host plant/larval host” content=”larval hosts”], while Skippers favor grasses. The California dogface caterpillar (Zerene eurydice) is found exclusively on California false indigo (Amorpha californica). Other caterpillars have a more expansive diet. The Small Cabbage White caterpillar (Pieris rapae) feeds any plant in the sulfurous brassica family like broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, and many other garden favorites. Oaks and willows are host to several butterfly species.

Most caterpillars thrive best on [glossary term=”native”] plants, however some have partially or even largely switched to exotic hosts. For example, the Anise Swallowtail caterpillar (Papilio zelicaon) is frequently found on Mediterranean fennel, an abundant weed found along roadsides and in empty lots. When it was proposed to eliminate fennel from San Francisco some years ago, butterfly lovers protested the loss of valuable habitat for the swallowtail.

The Xerces Society, an insect conservation organization, was named after another butterfly once found in the San Francisco dunes, the now-extinct Xerces Blue (Glaucopsyche xerces). The fate of the Xerces Blue is representative of the danger many butterfly species face today; more than 20 are threatened in California alone. Dr. Art Shapiro, a lepidopterist at the University of California, Davis, has studied regional butterfly populations for over 25 years and has seen a general decline in the numbers of many species. While some decline appears to be caused by climate change, much is attributed to habitat fragmentation and loss.

Thankfully, public awareness of the plight of these charismatic insects is increasing. Several national organizations are involved in butterfly conservation and local efforts abound. The Xerces Society has a nationwide campaign to increase habitat for Monarch butterflies with milkweed plantings. In San Francisco, the Green Hairstreak project seeks to increase urban habitat corridors for butterflies, and the green roof of the California Academy of Sciences includes both larval host and nectar plants. Close to my home in Sonoma County, Louise Hallberg’s enchanting butterfly gardens provide habitat for over 40 species of butterflies—and caterpillars—attracting thousands of visitors annually.

The novelist Vladimir Nabokov was enraptured by butterflies, particularly the Blues. In pursuit of his entomological passion, he collected Blues all over North America and Europe and went on several expeditions to South America. Nabokov proposed an original and complex hypothesis for the origin and evolution of the New World Blues. Although dismissed by lepidopterists of his day, Nabokov’s [glossary term=”taxonomy”] has recently been supported by new molecular genetics techniques. I will leave others to debate whether Nabokov was foremost a lepidopterist or an author, and simply enjoy the frequent references to his favored insects in his books.

In a Nutshell:

Popular Name: Butterfly.

Scientific Name: Families of butterflies found in the West include Brush-Footed butterflies(Nymphalidae); Whites and Sulphurs (Pieridae); Swallowtails (Papilionidae); Gossamer-Winged, including Blues, Coppers, and Hairstreaks (Lycaenidae); Metalmarks (Riodinidae); and Skippers (Hesperiidae).

Common Species: North American butterflies included in text: Nymphalidae: Monarch (Daunus plexippus); Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui). Pieridae: California Dogface (Zerene eurydice); Small Cabbage White (Pieris rapae). Papilionidae: Pipevine Swallowtail (Battus philenor); Anise Swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon). Lycaenidae, subfamily Polyommatinae (Blues): Acmon Blue (Plebejus acmon).

Distribution: Representatives of all of the above families are found throughout the West. Some butterflies, such as many Blues, are highly restricted in distribution, while others have a wide range. Painted Lady butterflies are almost global in distribution. Monarch and Painted Lady butterflies are known for their spectacular migratory behavior.

Life Cycle: holometabolous (complete metamorphosis).

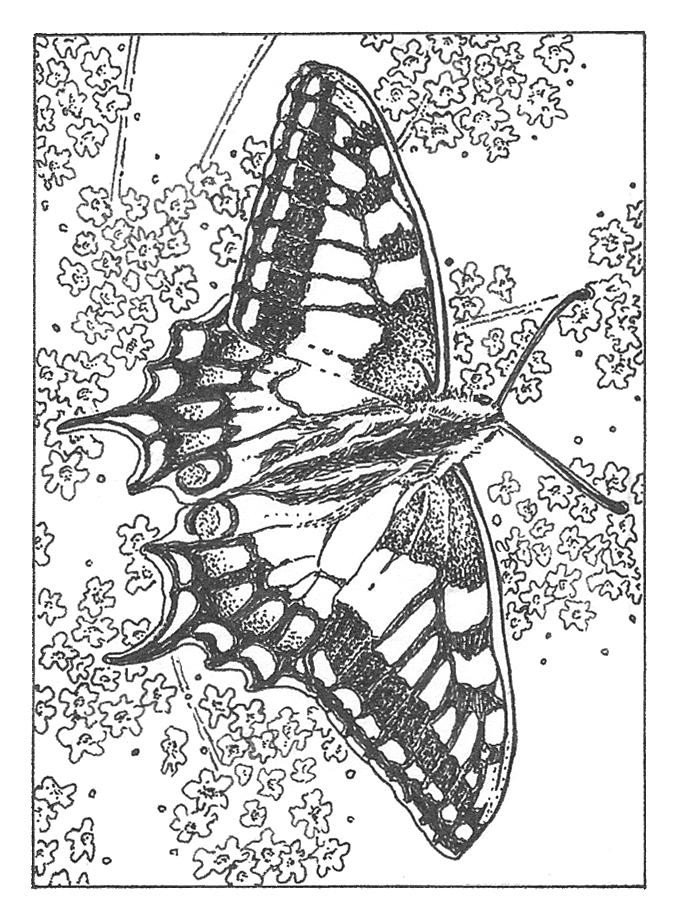

Appearance: Eggs: Spherical or ovate, laid singly or in clusters on larval host plants. Larvae: Caterpillars have three pairs of true legs and five or six pairs of prolegs. Pupae: Known as a chrysalis in Lepidoptera; butterfly pupae are the hardened final exoskeleton of the caterpillar. They vary greatly in appearance. Adults: Two pairs of scale-covered wings, often brightly colored.

Life Span: Typically, one or two generations a year in temperate climates. During warm months, each stage may last a few days to a few weeks; Monarch adults may live nine months. The overwintering stage, which varies with species, may last several months.

Habitat: Where larval host plants and suitable flowers for nectar feeding are abundant.

Diet: Caterpillars are highly specialized, requiring specific larval host plants. Adults feed on flower nectar or sometimes rotting fruit; some obtain minerals from mud puddles and excreta of other animals.

Favorite plants: Tubular flowers that provide a landing platform, generally colored red, yellow, pink, or purple. Many plants in the Asteraceae attract butterflies, as do verbena, yarrow, and Buddleia.

Benefits: Caterpillars are a critical food source for many birds. Butterfly watching can be enjoyed in the home garden.

Problems: Some species of ornamental plants can be severely damaged by caterpillars. Avoid using BT (Bacillus thurengiensis) which indiscriminately kills all caterpillars or only use on targeted plants on still days.

Interesting facts: Many Lycaenid butterfly species have a mutualistic relationship with ants. Some are parasitic, feeding on ant secretions, or predatory, feeding on ant larvae; the ants in turn protect the caterpillars of the Acmon Blue from which they obtain nectar-like secretions..

More information check out the following online resources:

Art Shapiro’s Butterfly Site, Hallberg Butterfly Garden, Xerces Society, Cultural Entomology Digest (see butterflies),

Butterflies and Moths of North America, Bringing Nature Home (Doug Tallamy), Vladamir Nabokov NY Times article,

Information on the Blues (Wikipedia)

Responses