Garden Allies: Lacewings and Their Kin

Contributor

Delicate Wings, Voracious Appetites

When I was a small child, my father showed me a leaf plucked from the backyard apple tree. Flipped over, it revealed a few trembling inch-long threads, tipped with delicate pearls. I well remember my amazement upon learning that these were the improbable eggs of green lacewings. Years later, in a college entomology course, the instructor held up a leaf bearing similar graceful eggs; before he could say “who knows what kind . . .” I recognized not only the eggs, but my life-long wonder at nature’s backyard marvels.

Variations on a Theme

The order Neuroptera includes green and brown lacewings, dustywings, antlions, owlflies, and mantidflies. Snakeflies are now placed in a separate order, the Raphidioptera, and dobsonflies, fishflies, and alderflies in the Megaloptera. All three orders may be grouped as the superorder Neuropterida. We focus here on the most useful from the gardener’s point of view: the lacewings (green and brown), dustywings, and the snakeflies.

Green lacewing (Chrysopidae) adults are familiar to most gardeners. Their diaphanous, mint green wings blend into foliage; coupled with their primarily nocturnal, and sometimes arboreal habits, they are infrequently seen, although they may be attracted in numbers to porch lights. The smaller and more often nocturnal brown lacewings (Hemerobiidae), and curious long-necked snakeflies (Raphidiidae), may also be spotted by observant gardeners, but minute dustywings (Coinogypteridae), if noticed at all, are usually mistaken for whiteflies—a rather less welcome denizen. Most neuropterans are predatory as larvae, and many also as adults, although some adults feed exclusively on pollen, nectar, and honeydew (the sugary excretion produced by aphids and other homopterans). The gardener may come across green lacewings and snakeflies visiting blossoms during the daylight hours. Depending on the species, lacewings and their kin prey on all sorts of arthropods, including homopterans such as aphids, scale insects, whitefly, mealybugs, and other prey such as spider mites, various insect eggs, beetle larvae, thrips, and small caterpillars. Some species are known to detect the larvae of leafminers, and pierce the leaves to reach their prey.

Green Lacewings

Resembling tiny whitish alligators, the larvae of green lacewings are generally found among their somewhat sedentary prey (often aphids). The mandibles are equipped to pierce prey, injecting a paralyzing, liquefying venom that enables the larva to suck out the victim’s fluids. Some species of green lacewings camouflage themselves with debris such as bits of plant material, their own excrement, and even the empty hulls of their victims. Last fall, a cleverly disguised “wolf in sheep’s clothing” caught my eye: a well-fed lacewing larva among a colony of mealy bugs, looking just like another mealy-bug, its speed and well-developed legs gave it away. It is thought by some scientists that the larvae are in disguise, not to make them invisible to their prey (who seem oblivious to the presence of a “wolf” in their midst) but to camouflage them from their own predators. The voracious larvae may eat hundreds of pests during their development. Depending on the species, adults may be omnivorous (eating pollen and nectar in addition to prey), or may live exclusively on floral foods.

Brown Lacewings

Although smaller and drab-colored, brown lacewings are readily recognized by alert gardeners. The eggs are laid singly on leaves or bark, usually in arboreal habitats. The larvae are similar to those of green lacewings, but with less prominent mandibles. Brown lacewings are important beneficial insects, as both adults and larvae are predators, primarily of homopterans such as scale insects, aphids, and whitefly nymphs. Many species of brown lacewings are restricted to certain plants, suggesting that they may be specialist predators. With their long lives, high reproductive capacity, and voracious appetites, they may one day prove useful in commercial biological control, but they are not now commercially available.

Dustywings

When I first noticed dustywings, in an ornamental purple-leaved plum, I thought I was looking at whiteflies. Dustywings are easily distinguished from whiteflies by their wing position at rest, exhibiting the typical “roof” shape of the lacewings (whiteflies hold their wings much flatter). A crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) tree-dweller, this tiny predator is known for its appetite for spider mites, as well as scale insects and arthropod eggs. The tiny larvae resemble minute lacewing larvae. More common than once thought, dustywings are found primarily in warmer parts of the Pacific Northwest. Despite their usefulness, they are also commercially unavailable.

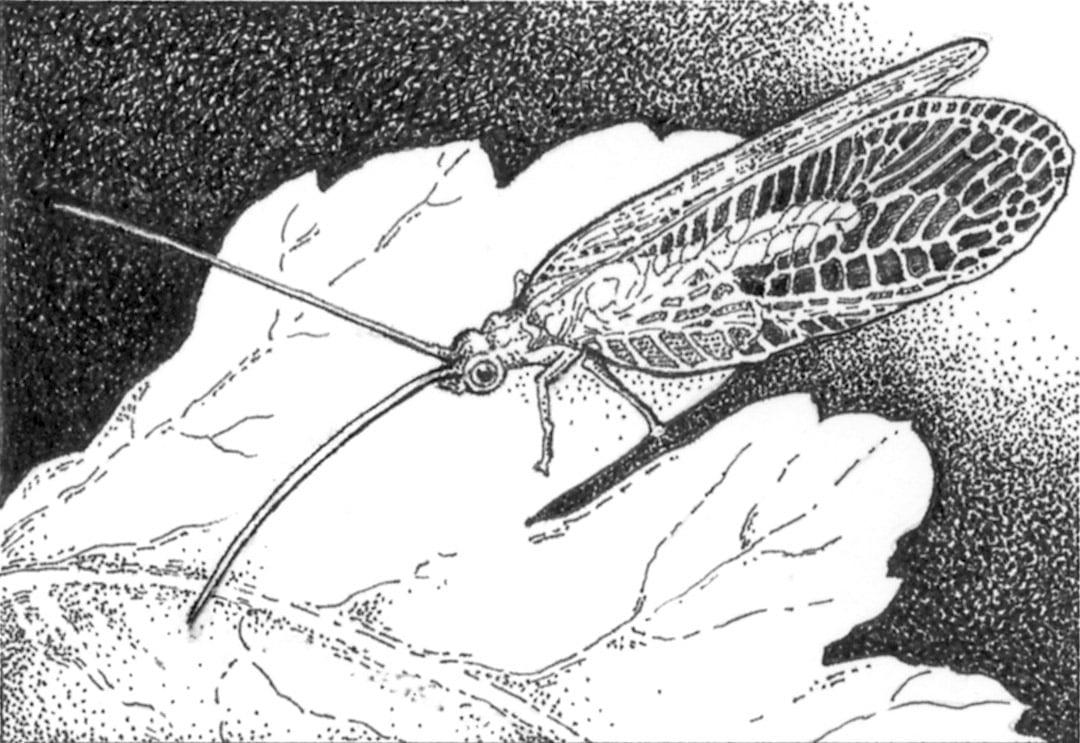

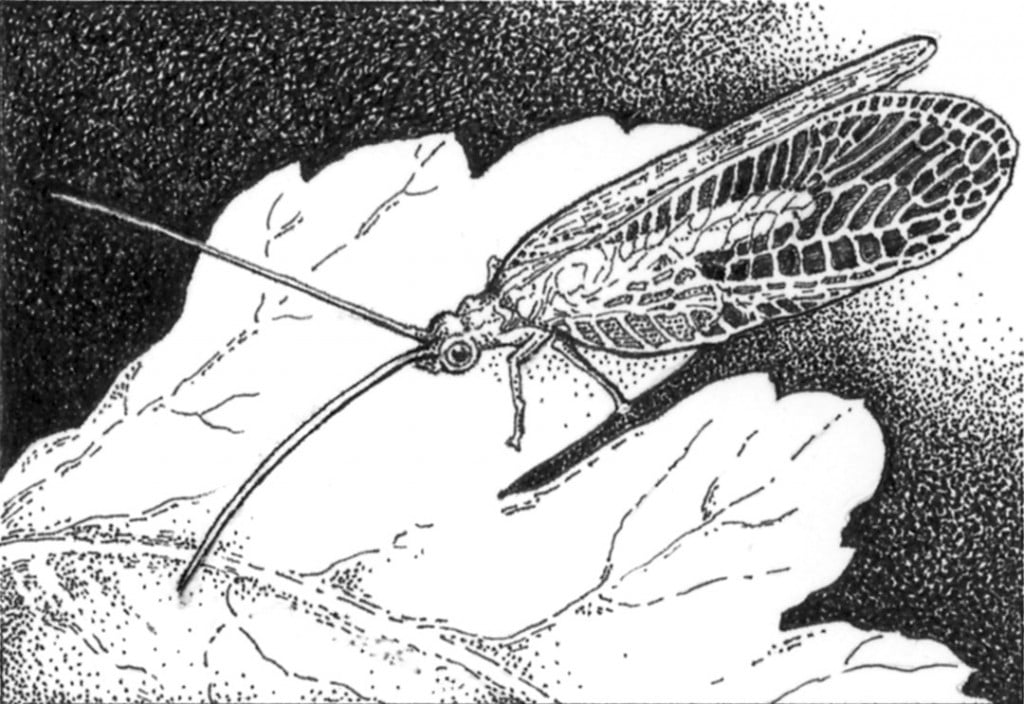

Snakeflies

Snakeflies invariably provoke a response from anyone who sees them for the first time. They have elongated “necks” and heads that can turn like a praying mantis; females have a long ovipositor that looks like a stinger. The peculiar larvae, sometimes found under bark, have a habit of running backwards when startled; adults can be spotted visiting flowers. Snakeflies, predatory as both larvae and adults, may be of great value in the garden environment.

In the Garden

A garden is an ideal environment for supporting populations of a diversity of lacewings and related allies. Encourage these valuable predators by providing layers of trees and shrubs, annuals and perennials, as Neuropterida inhabit many niches in the garden. As with many garden allies, biodiversity is also encouraged by developing a landscape with many kinds of plants, producing flowers over a long season.

Recently, a friend recommended that anyone obsessed with insect observation (did she mean me, I wondered?) would be well advised to acquire a pair of the close-focusing binoculars popular with butterfly enthusiasts. Watching the lacewings on my flowers, with their delicate shimmering wings and great golden eyes, I am glad to have taken her advice.

In a Nutshell

Popular Names:

Lacewings (aphis-lions), dustywings, snakeflies

Scientific Name:

Superorder: Neuropterida. Order: Neuroptera (green and brown lacewings, mantidflies, antlions, owlflies and dustywings). Order: Raphidioptera (snakeflies). Order: Megaloptera (fishflies, dobsonflies and alderflies).

Common Species:

Green lacewing (Chrysoperla carnea), brown lacewing (Hemerobius spp.), snakefly (Agulla spp.).

Distribution:

Worldwide, about 6,000 species in Neuroptera, about 150 species in Raphidioptera.

Life Cycle:

Holometabolous (complete metamorphosis from egg to larva, pupa, and adult). Females may lay up to 200 eggs.

Appearance:

Common green lacewing (other neuropterans may vary, but all have the characteristic net-veined wings as adults): Eggs: white or pale green orbs, perched on a delicate filament, generally under leaves. Larvae: brown or grey, look like tiny alligators with large mandibles. Pupae: cottony, attached to plants. Adults: Pale green with golden eyes, long thread-like antennae, and transparent green wings, about 12-20 mm (.5-.8”) long. Brown lacewings are 10-15 mm (.4-.6”), snakeflies are 12-25 mm (.5-1”), dustywings are only 2-5 mm (.08-.2”).

Life Span:

Life cycle of neuropterida is influenced by temperature; four to six weeks is not unusual in good weather; some species may produce several generations per year in mild climates; other species live for more than a year.

Diet:

Many common garden species eat insects and other small arthropods, including aphids, thrips, leafminers, small caterpillars, beetle larvae, whiteflies, leafhopper eggs, spider mites, and mealybugs. Some adults do not feed, or feed only on nectar.

Favorite plants:

Adults of many (including green and brown lacewings and snakeflies) can be found visiting nectar-producing, small-flowered plants such as members of the daisy and carrot families (Asteraceae and Apiaceae).

Benefits:

Active predators of many small pests, some species are reported to eat as many as 100-600 aphids each in their larval stage.

Problems:

Wishing we had more!

Interesting facts:

Green lacewings lay eggs at the ends of “stalks” in order to prevent juvenile cannibalism of the eggs by their own freshly hatched, voracious larvae.

Sources:

Green lacewings are readily available commercially and may be shipped in any life stage; best added to gardens as eggs. Other Neuropterida are unavailable; provide suitable habitat, nectar and pollen resources to encourage their presence. Some species of lacewings overwinter as adults, often in leaf litter.

More information:

A useful website is www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/NE/index.html, the UC Davis IPM Natural Enemy Gallery.

Lots of Insects by Frank E Lutz (1941), former curator of the entomology collection at the American Museum of Natural History is an engaging look at many species of backyard insects, with a wonderful chapter on antlions and their curious lifestyle, and a description of how those wonderful green lacewing eggs are produced. (Out of print; request it from your local library.)

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Calochortophilia: A Californian’s Love Affair with a Genus

Summer 2022 I can chart the progression of my life by Calochortus. For the last two decades, at least. As a teenage girl growing up

Pacific Plant People: Carol Bornstein

Spring 2022 Public gardens play a key role in demonstrating naturalistic planting design, selecting native and adapted plants for habitat, and testing techniques for reducing

Add Year-Round Interest and Winter Blooms for Pollinators

Spring 2022 This article was created from an Interview by Merrill Jensen with Neil Bell in the Summer of 2021 for our Pacific Plant People

Responses