Landscape Design for Fire Safety

Contributor

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire. . .Robert Frost, “Fire and Ice”

California—and much of the West—is designed to burn. All it takes is a spark from a downed power line or a power mower, a hot muffler, a carelessly tossed cigarette or match, a firecracker, or an untended campfire to ignite a fast moving grass fire that can erupt into an inferno.

In California’s mediterranean1-type climate, environmental characteristics combine to create a potential fire hazard for people who live in the urban-wildland interface on the edges of cities, in suburbs, and in communities that are rapidly expanding into foothills and mountains. The desire for views, for large lots to ensure privacy, and for woodland settings, in an environment in which fire is a natural and recurrent force, establishes the framework for fire hazard.

1 The word mediterranean (lower case) refers generically to mediterranean-type climate, vegetation, and other features of the various mediterranean zones of the world. Mediterranean (capitalized) refers to the geographic region of the Mediterranean Sea.

By early to mid-summer, soil moisture is nearly depleted, the growing season essentially over. Native plants have adapted to such an inverted cycle (as compared to a temperate climate with summer rainfall) by entering a state of summer dormancy. Some plants shed most or all of their foliage. Moisture level in plant tissue is lowered as summer heat and lack of available soil moisture increases. By mid- to late summer, the mostly evergreen vegetation (both broadleaf and coniferous) becomes tinder dry, with a considerable accumulation of dead material. In autumn, relative humidity often drops to as low as ten percent, when hot, dry offshore winds desiccate the land and create “fire weather.”

Many mediterranean plant species, both native and introduced, have adapted to summer drought in ways that contribute to their flammability. Pines and other conifers contain volatile resins, while such plants as eucalyptus and manzanita contain volatile oils. Many drought-adapted plants, such as conifers, chamise, manzanita, coyote brush, sage, and some ceanothus, have small leaves. Smaller leafed plants such as these are more likely to burn than broader leafed plants, especially when moisture content is low.

A century of fire suppression throughout the West has resulted in a massive build-up of tinder dry fuel. This is compounded by decades of low precipitation. Serious diseases have further devastated the weakened forests: pine pitch canker and sudden oak death in the north and insect damage to ponderosa pine forests and eucalyptus groves in the south. Once a fire starts, especially in chaparral, a conflagration can develop. In oak woodlands and forests, the accumulation of dead or dying trees and underbrush combined with the spread of flammable, invasive exotic trees and shrubs (gorse, broom, pampas grass, acacia, eucalyptus and many others) contributes to the fuel load by creating a fire-ladder effect that can permit a low grass fire to rise into the tree canopy.

Fire Safe Design Principles

The guidelines presented here are primarily aimed at relatively light fires, such as grass and brush fires. Once a small fire has erupted into a conflagration, little can be done to prevent complete devastation. Wind-blown fire brands (flaming embers) can be carried up to a mile from the fire to increase its spread. The intensity and length of flames can ignite anything in its path, even moving into densely populated urban areas, as has happened in Oakland (1991) and in southern California communities (2003). Even the best design and vegetation management would prove ineffective in such catastrophic wildfires.

While there are no guarantees that homes and gardens can be made completely safe from a conflagration, especially in over-mature chaparral, much can be done at both the site and community level to reduce fire hazard. Two basic principles guide the creation of a fire safe landscape: the reduction of fuel and the interruption of a fire’s path to create a “defensible space.”

Fuel Reduction

Fuel is anything flammable that will contribute to the spread of a fire, including dead or dry vegetation, highly flammable plants, plant litter, firewood, miscellaneous scrap wood or stored lumber, and wooden structures such as fences, decks, and arbors. For the purposes of this discussion, structures are excluded, although their design and placement are key factors in fire safety. (See box, page 8)

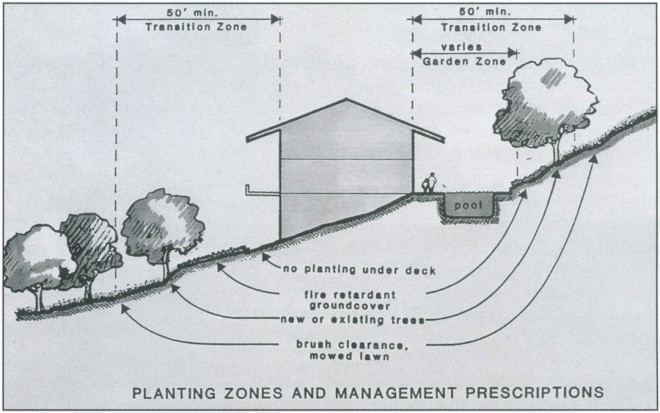

Fuel should be reduced within a zone ranging from thirty to fifty feet (one hundred feet or more on steep slopes and in dense vegetation) from a home or other structure. Within this zone, reduce fuel by:

- mowing dry grasses to four inches after rains have ceased, usually in June

- removing dead and dry brush such as coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis) and chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) and maintaining other brush under two feet in height

- removing any excessive accumulation of dry leaf litter and duff

- thinning out trees so canopies do not touch

- thinning existing, or planting new, shrubs in widely detached islands

- removing highly flammable trees such as pines, other conifers, and blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus)

- raising the crown of trees to at least fifteen feet above ground, and ten feet over roofs, to reduce the fire ladder effect

- replacing wood fences with wire mesh fencing

- removing invasive exotic plants that are highly flammable, such as broom (Cytisus), pampas grass (Cortederia), and Cotoneaster

If a thirty-foot fuel reduction zone is not possible on a smaller property, many of these methods can still be effectively employed. Remove dry grass and brush along a street or road; remove highly flammable plants such as blue gums, junipers, and most conifers; and prune trees as suggested.

[sidebar]

Site Planning and Construction Techniques to Protect Against Fire

1. Enclose the structure of decks, roof overhangs, cantilevered houses, carports, and garages.

2. Use nonflammable materials, such as stucco, concrete, or masonry to clad buildings and tile or other nonflammable roofing materials.

3. If possible, buildings should be set back fifty to one hundred feet or more from the prow of the top of a hill. Combined with the construction of a non-flammable wall at the top of the slope, such a setback may be able to protect a house from flames sweeping up a grass or brush-covered slope.

4. Houses and other structures should not be sited in or at the head of a canyon or ravine. These are the most hazardous locations, because a ravine or canyon acts as a chimney drawing fire upward. Even radiant heat from a fire on the opposite slope across a canyon can penetrate windows of a house and ignite the building from inside. In such a setting, the installation of retractable exterior metal shutters could be effective in protecting windows.

[/sidebar]

Creating Defensible Space

A number of strategies can be employed on all but the smallest sites to interrupt the path of a fire and create a defensible space around a home or other structure. These strategies include both design concepts and landscape management practices.

Zoned Landscape:

For large properties in or adjacent to a natural landscape, zoning a property into three landscape zones can serve as a framework for protecting home and garden from a potential fire. The garden zone is a compact area or areas adjacent to the house, wherein there is moderate water use for irrigation of relatively lush plantings; this zone is the appropriate location for pools and patios.

Beyond the transition zone is a fire protection zone planted with fire- and deer-resistant plantings; the natural vegetation is carefully managed (see Fuel Reduction, above). Only native trees are planted here, and flammable invasive exotics, such as broom, are removed. Further from the home is the natural landscape zone, where natural vegetation is managed, as above, for fire protection.

In addition, non-flammable garden walls enclosing the garden zone may stop a fire from reaching the house. Masonry and concrete are good materials for retaining walls. For freestanding walls, masonry, stucco over wood, or rammed earth can be used to create handsome enclosed terraces or courtyards.

Firebreak:

Creating a bare soil firebreak is commonly done in grassland areas and on ranches to check the progress of a grass fire. Such a technique may not be possible or feasible on a smaller residential site, especially on slopes where erosion is a problem. An alternative method is to create broad paved paths to act as a firebreak and to serve as access to the site or garden; their value will be limited to relatively small ground fires.

A firebreak does not preclude planting or maintaining trees. Shade is essential in a mediterranean climate and a desert environment. But the selection and management of trees must be done with fire safety principles in mind: selecting relatively fire-resistant trees, pruning to avoid a fire ladder effect and to clear rooptops, spacing trees so canopies do not touch.

A firebreak of vegetation can also be effective if carefully planned and managed. Fuel reduction techniques listed above can slow the progress of a ground fire in the natural landscape zone. In the transition zone and at the edge of a garden area, the planting of certain plants that are relatively resistant to burning can further retard an advancing ground fire, though such planting must be irrigated to retain sufficient moisture content in the foliage.

Planting for Fire Resistance:

Although any plant will burn if hot enough, many plants are able to resist fire by not burning or by burning slowly enough to provide a means of disrupting the path of a relatively mild fire. A complexity of factors influence the degree of fire resistance in these plants: soil moisture and plant tissue moisture, plant structure, size, age, foliage type, and plant health. The most fire resistant plants are succulents that store water in fleshy tissue, but even these types of plants will burn if that moisture is depleted by an extremely hot fire.

Irrigated turfgrass effectively disrupts the spread of a ground fire. However, large expanses of lawn wastewater in arid areas, appear incongruous in the natural landscape setting, and can give a false sense of security if other fire safety precautions are not employed. Many groundcover plants such as ivy (Hedera) and periwinkle (Vinca) are relatively resistant to burning if moisture level is kept high through occasional irrigation. A good alternative to lawn is a groundcover of unmown fescue (Festuca rubra, F. californica, or F. idahoensis).

Planting fire resistant trees, shrubs and ground covers in the garden and transition zones surrounding a house may help retard an encroaching fire and airborne fire brands. To maintain high moisture level in these plants and to reduce weeds, such planting should be irrigated, preferably by drip emitters. Even some “fire-resistant plants” can become highly flammable when their moisture level drops. Most drought-tolerant landscape shrubs can survive on an average of one-half inch of water per week during summer but may require slightly more to improve appearance.

Planting for fire resistance is not incompatible with landscape water conservation. Many fire-resistant plants, such as dwarf coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis ‘Twin Peaks’), Australian saltbush (Atriplex spp.), creeping sage (Salvia sonomensis), and many others, are also drought tolerant. For these plants, maintaining the moisture level for maximum fire resistance should not result in excessive water use if a drip system is installed and programmed according to water requirements.

The use of plants listed as “fire-resistant” to create firebreaks or defensible space must be coupled with all the other design and maintenance recommendations to be reasonably effective. Even then, there is no guarantee that plants will be completely effective in combating an intense, wind-driven wildfire.

Supplemental Sprinklers:

The installation of a separate line of impact-type sprinklers on the edge of the transition zone can be effective in helping stop a fire’s progress. However, such a system may not work if connected to the city water supply. Water pressure can drop due to the draw by fire fighters and render a line of emergency sprinklers ineffective. Conversely, their use can hamper fire fighting by reducing pressure in the main lines.

Where the source of water is from a well, electrical power to run the pump may be cut off in a fire. A propane or gasoline powered generator can provide auxiliary power to operate the well pump to ensure water flow to the sprinklers.

Additional Water Sources:

Supplementary sources of water to help suppress a fire should be considered in the design of gardens in fire-prone areas. A swimming pool (average capacity of 20,000 gallons) can become an effective water reservoir if a gasoline powered pump and fire hose is used.

Rainfall, harvested from roofs and pavements and stored in cisterns made of inexpensive plastic tanks, can be used for supplemental irrigation of the fire-resistant plants in the transition zone. A capacity of about 5,000 gallons can be effective in reducing landscape water use and maintaining a relatively lush greenbelt around the house. By building a cistern system into the house initially, considerable savings and efficiency can be realized.

In rural areas where there is no city water supply, properties have wells and usually water storage tanks with capacities up to 10,000 gallons. These tanks can be fitted with valves and connectors that a fire truck can tap into to fight a fire.

Conclusions

Living in a mediterranean climate is alluring for most people. Sweeping vistas of deep blue water or picturesque hills and a benign climate with nearly endless sunshine belie the challenges and hazards of this habitat. Fire cannot be ignored as a natural force in mediterranean shrublands and woodlands. Its immense power and incalculable dire effects require that all who plan, design, build and live in this environment must make changes to reduce the risk. The consequences of doing nothing are made painfully clear each year.

Designing residential landscapes for fire safety is equal parts social attitude and the techniques of site design and vegetation management. The technology is well known and relatively easy to implement. But attitudes are difficult to change from complacence and denial to acceptance of the realities of living in fire hazard areas. As vegetation management consultant Carol Rice has stated about changing our attitudes, “You can pay now, or pay later.” She states that people’s attitudes must shift from: “we haven’t had a fire in eighty years, so why worry?” to “we haven’t had a fire in eighty years, so we’re especially worried.

[sidebar]

For Further Reading

EBMUD. 2003. Firescape, “Landscaping to Reduce Fire Hazard.” Oakland: East Bay Municipal Utilities District.

Moore, Howard E. 1981. Protecting Residences From Wildfires: a guide for homeowners, lawmakers, and planners. General Technical Report PSW-50. Berkeley: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station.

Pyne, Stephen J. 1982. Fire in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Pyne, Stephen J. 1984. Introduction to Wildland Fire, Fire Management in the United States. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Radtke, Klaus W. H. 1982. A Homeowner’s Guide to Fire and Watershed Management at the Chaparral/Urban Interface. Los Angeles: USDA Forest Service and County of Los Angeles.

Rice, Carol L. and James B Davis. 1991. Land-Use Planning May Reduce FireDamage in the Urban-Wildland Intermix. General Technical Report PSW-127. Berkeley: USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station.

[/sidebar]

Factors That Influence Fire Resistance in Plants

Soil Moisture and Plant Tissue Moisture: The time of year in dry climates is an important factor influencing fire resistance. In early summer, after the last spring rains, most plants have high moisture content and are thus more fire resistant than later in the season with no rain or irrigation. An example is California bay (Umbellularia californica): in early summer, it is quite fire resistant, but by autumn, its moisture level is depleted (unless growing in the moist soil of a streambed) and it becomes rather flammable.

Both soil moisture and plant tissue moisture can be depleted rapidly as temperatures increase and humidity drops. This is exacerbated by windy conditions that can desiccate plant tissue. Usually this combination of conditions occurs at the end of summer and in early fall, but hot, dry periods can occur in early summer, leaving plants abnormally susceptible to fire. Supplemental irrigation is necessary to retain both soil and tissue moisture levels through the long summer and fall. However, care must be taken to avoid over-irrigating plants, thereby causing excessive growth that can add fuel during fire weather. Summer-dormant, drought-tolerant plants that are also fire resistant require little, if any, additional irrigation. Excessive irrigation can kill some summer dormant species such as flannel bush (Fremontia spp.), thereby adding dry fuel.

Plant Structure: Plants that have a compact habit of growth are more fire resistant than those with an open structure. The low-growing, compact form of coyote brush (Baccharis pilularis ‘Twin Peaks’) is infinitely more resistant than the open shrubby upright form (B. pilularis subsp. consanguinea). Many low, compact forms of other native plants, such as manzanita (Arctostaphylos) and ceanothus can be effective if moisture levels are maintained through drip irrigation.

Size: Low growing plants that are also compact are more resistant than taller plants. On the other hand, very tall plants that are pruned up to a height of about fifteen feet or more, and have no loose bark that might create a fire ladder, can resist low, ground fires. Many mediterranean oaks are adapted to ground fires due to thick, resistant bark.

Age: Young plants that are growing vigorously contain more moisture than older, less vigorous plants, especially those that are approaching senescence. Old plants usually have a considerable amount of dead wood and may contain dead leaves or needles that remain on the plant or build up on the ground beneath. Such plants require periodic pruning to remove flammable dead material. Shrubs that will crown sprout can be cut back to the ground periodically to renew growth.

Leaf Type: Broad, fleshy leaves tend to burn more slowly in a fire than small leaves such as the needles of conifers and the slender blades of grasses. Most broadleaf deciduous plants are relatively fire resistant as are many broadleaf evergreens with large, fleshy leaves. Succulents, with their fleshy leaves and stems, are among the most fire resistant of all plants.

Health: Maintaining plants in a healthy condition is a key to their resistance to fire. Even the most fire resistant plants, if stressed from drought or disease, will be susceptible to burning due to the loss of tissue moisture and an increase in dead wood and leaves.

Numerous lists of plants that are regarded as “fire resistant” or “fire tolerant” have been published. Some disagreement exists among these lists. Many are based on anecdotal information with little scientific evidence; little real testing has been done to verify each plant’s fire performance. The Forest Products Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley, has begun testing some plants. As a first step, the lab has reviewed numerous lists and compiled its own list of plants that have been given a favorable or unfavorable rating on fire performance by at least three referenced sources. Of a total of 598 species in this list, 147 had a favorable rating, seventeen were unfavorable, and fifty-three had conflicting ratings. Their Vegetation Guide is available on-line at the lab’s website (www.ucfpl.ucop.edu/I-Zone/XIV/vegetati.htm). Additional guidelines for developing fire safe landscapes and dwellings are also available at their home website (www.ucfpl.ucop.edu).

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Ground Up Science for Greener Cities with Garden Futurist Dr. Alessandro Ossola

Spring 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. Alessandro Ossola is a scientist who gets very excited about the challenge of climate change allowing for an

Readying Urban Forests for Climate Realities with Garden Futurist Dr. Greg McPherson

Winter 2023 Listen to the Podcast here. “Going from the mow and blow to a more horticulturally knowledgeable approach to maintaining the landscape. And that

Low Maintenance Gardens – Better for Pollinators and People

Autumn 2022 “I come out every day. It’s therapy, my meditation.” Janet’s young garden transformed from overgrown, invasive plants to mostly natives. The dailiness of

Invasive Plants Are Still Being Sold: Preventing Noxious Weeds in Your Landscape

Autumn 2022 With so many beautiful ornamental plant species and cultivars throughout California and the Pacific Northwest, how do you decide which ones to include

Responses