From the Ground Up: Part 2 Excerpt

Contributor

- Topics: Drought and Fire Resilience

Spring 2022

From: From the Ground Up by Alison Sant. Copyright © 2022 Alison Sant. Reproduced by permission of Island Press, Washington, D.C.

For decades, American cities have experimented with ways to remake themselves in response to climate change. These efforts, often driven by grassroots activism, offer valuable lessons for transforming the places we live. In From the Ground Up: Local Efforts to Create Resilient Cities, design expert Alison Sant focuses on the unique ways in which US cities are working to mitigate and adapt to climate change while creating equitable and livable communities. She shows how, from the ground up, we are raising the bar to make cities places in which we don’t just survive, but where all people have the opportunity to thrive.

Nature-Based Solutions

Cities throughout the United States are using green infrastructure to make natural systems the core of stormwater solutions. Approaches involve a strategically planned network of natural areas that use ecological processes to improve water quality and restore the hydrologic function of the urban landscape while protecting biodiversity, providing ecosystem services, creating verdant public spaces, and increasing resilience to flooding and other climate risks. [16] Portland, Oregon, created one of the first green infrastructure programs in the United States in the 1990s (see chapter 5).

Green roofs, rain gardens, bioswales, and trees all help make cities more permeable. Plazas and parks can provide areas for water to be captured and released slowly. Residents can make their yards porous, install rain barrels, and disconnect their downspouts. These projects are designed to manage stormwater where it falls, allowing it to penetrate the ground or evaporate into the air. They mimic natural systems by designing buildings, parks, and roads to perform like trees, lakes, and streams. Green infrastructure often separates urban sewage systems from stormwater systems, allowing water to be absorbed, saved, and reused.

It is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Successful green infrastructure solutions have come from piloting approaches, monitoring them carefully to learn what works, and applying them to specific sites before scaling them up. Cities like Portland are finding that their greatest asset in designing effective green infrastructure is having a large and varied toolbox of solutions that can be applied to different geological and hydrological conditions as well as a diverse urban fabric (see chapter 5). After thirty years of work, green infrastructure is ubiquitous in Portland. Matt Burlin, environmental program coordinator for the city, said that green infrastructure has “evolved past progressive thinking to practical thinking.” [17] It is routinely a part of making a city with greener streets, verdant public places, cooler neighborhoods, and affording the chance to swim in the Willamette River.

Chapter 5: Portland

Watershed Planning

Tabor to the River

Tabor to the River, a pilot project on the southeast side of the city, created an innovative stormwater management approach to provide best practices, which can be adapted and applied to other basins in the city. Extending from Mount Tabor, a dormant volcano, to the banks of the Willamette, the project crosses the Richmond, Hosford-Abernathy, Brooklyn, and Mount Tabor neighborhoods. The project covers more than 2 square miles of a dense urban landscape. With high average rainfall in Portland and increased development draining stormwater and wastewater into an aging combined sewer system, sewer backups have been a problem in the past. [56] To alleviate some of these backups, the city looked to smaller green infrastructural interventions on public and private lands to help remove surface water from the limited pipe system.

Tabor to the River was initiated by BES in 2009 as a fifteen-year project. It aims to plant 3,500 trees, add 500 green streets, and build 100 stormwater projects on private land while repairing or replacing 81,000 feet of sewer pipe. [57] Green infrastructure was proposed in locations where gray infrastructure was most limited, helping divert stormwater from the system. Green infrastructure upgrades were funded by the Wet Weather Program, a $3.4 million granting program of the EPA to encourage innovative public-private partnerships in creating stormwater features throughout Portland. These projects demonstrate sustainable, low-impact stormwater management solutions while providing facilities for traffic calming, bike parking, placemaking, and community building. [58] New Seasons Market was one of the first businesses in the neighborhood to adopt nature-based approaches. The project processes stormwater from its site, as well water on neighboring streets, through interconnected stormwater swales and planters that encircle the building and parking lot. Runoff from the rooftop, parking lot, sidewalks, and streets is captured through this system, slowed, and filtered as it enters vegetated areas, where it infiltrates the ground. The facility prevents more than 500,000 gallons of stormwater runoff from entering the combined sewer system annually. [59] Examples of bioswales, rain gardens, storm-water planters, eco-roofs, drought-tolerant landscaping, street trees, and disconnected downspouts are scattered throughout the surrounding neighborhood. [60] According to Burlin, “We are avoiding having to build a bigger project, a more complicated project, and one that is more expensive and harder to maintain by engaging property owners on their own property.” [61] Residents help manage stormwater through the Private Property Retrofit Program. The program created a precedent that managing stormwater did not have to be limited to publicly owned land. [62] The city could capitalize on investments in private property solutions that helped reduce the load on the system, reduce the city’s long-term maintenance and operating costs, and save the ratepayers money. [63] Through the program, homeowners volunteer to work with the city to design, install, and maintain systems on their property using green infrastructure. The program helps mitigate flooding, reduce sewage treatment costs, replenish groundwater supplies, and beautify neighborhoods

In 2010, the original pilot project began with eight neighborhood residents that installed rain gardens and planters in their yards. [64] Each garden was uniquely suited to its and the opportunities of the site, making the solutions diverse. This patchwork of small-scale approaches makes the neighborhood variegated and unique. Some of the gardens evoke wild wetland landscapes, whereas others are more sculptural, creating ponds or planter boxes to hold water. As opposed to large-scale, subterranean stormwater solutions that would be invisible to the community and have little ecological benefit within the neighborhoods they serve, these small-scale projects bring character to the fabric of a neighborhood and involve residents in the task of stormwater management. Although each one is small, together these gardens reduce 170,000 gallons of runoff annually. Through the Tabor to the River Program, this neighborhood approach was replicated on other local streets. Close to seven hundred residential and business owners participated in the first phase of the project, achieving 3.2 acres of new stormwater infrastructure for under $6 per square foot, compared with $8 per square foot for traditional gray infrastructure. In the public right-of-way, residents and businesses also participate in the Green Street Stewards program, helping maintain green street features. Community members adopt a street and are trained on how to maintain it. Stewards commit to plant and maintain rain gardens by keeping curb openings and drains clear to increase water flow, watering plants, and removing weeds. This level of community support comes from a very active set of neighborhood associations throughout Portland that give agency to local residents. [65] The city also partners with community groups. For example, Depave works in underserved communities to transform schoolyards and community centers. It has removed more than 220,000 square feet of impervious surfaces and reduced annual stormwater runoff by 15,840,000 gallons since 2007. [66] Friends of Trees, a local urban forest advocacy group, has planted 850,000 native trees and shrubs since 1989. [67] Often these partnerships are motivated by different goals, helping broaden the recognized benefits of greening the city. As Burlin said, “There’s a confluence of missions with our community partners. It’s not all driven by stormwater goals. We put in these green streets, they’re great stormwater facilities, but they also have ancillary benefits. Advocacy comes in a lot of shapes.” [68]

Creating a Livable City

Implementing green infrastructure in Portland has evolved from being a bold solution to managing stormwater to one of a set of approaches focused on creating a more livable city for all its residents. According to Burlin, “What we have learned is that a diverse set of tools is integral to solving complex, urban stormwater challenges. These tools do not change often, but how they are applied does. The tools can and should be used differently based on a neighborhood’s character, constraints, and opportunities.” [69] This growing tool kit has been built over decades by creating pilot projects, monitoring how they perform, and evaluating what worked.

Now it is being deployed throughout the city, based on what neighborhoods need. Through its 2035 Comprehensive Plan, updated in March 2020, Portland is looking ahead to how its green infrastructure successes can be utilized to create holistic solutions in which equity, economic prosperity, resiliency, and human health are interwoven. [70] In Portland, a history of racist land use policies has contributed to racial segregation and inequity for people of color. This history is compounded by rising housing costs that have pushed Brown and Black people to live in neighborhoods that lack basic services. [71] City agencies are pooling their resources to make comprehensive improvements to the public right-of-way, providing better service in these neighborhoods and directing city funding more equitably. Burlin believes that community-based organizations are the best partners for ensuring that local perspectives guide the city’s investments. [72] He said, “Having an engaged community that is aware, understands, and embraces these improvements is really important. And if you’re going to do that in an area where people lack adequate sidewalks, then you really need to consider pedestrian enhancements, which means you can’t be working in a vacuum.” [73] For example, if neighborhood streets and sidewalks flood, the problem is not only a stormwater management problem but also a transportation issue, as it blocks pedestrians from walking to the bus or cycling to work. These inconveniences affect safety and livability, especially in neighborhoods where most people do not own cars. BES and the Portland Bureau of Transportation began working together in 2008 to install green infrastructure alongside bike lanes and sidewalks. By aligning their services, these agencies have been able to identify gaps where investments can meet multiple goals in places that need them most. [74]

The Cully neighborhood, located north of the Johnson Creek Watershed in the Columbia Slough, is among these places. The majority of Cully’s residents are people of color, one-fourth of whom are Latinx people. [75] The neighborhood has scarce access to public transit, a lack of open space, unsafe sidewalks and streets, and substandard stormwater management systems. In 2010, Living Cully formed as a collaborative network to bring investments to the neighborhood while building jobs for local residents and fighting displacement through affordable housing and increased ownership. [76] As Cameron Herrington, Living Cully’s program manager, explained, “The people who have the most to gain, and potentially the most to lose, from neighborhood development are Black, Indigenous, and people of color, renters and mobile home residents, low-income people, immigrants, and people with disabilities. We bring people together, build relationships, discover the common challenges and threats that people are facing, learn about potential solutions together, and then take action to improve people’s lives.” [77] Among immediate improvements to the neighborhood are those to Cully’s streets. Verde, a community-based nonprofit organization and partner in the Living Cully network, has helped the community guide these investments and benefit from their installation. As Ricardo Moreno, a program manager at Verde, explained, “If you drive around the Cully neighborhood, you’ll find that a lot the streets are unpaved. There are no sidewalks, which creates high rates of accidents. People get run over by cars because there are no stoplights.” [78] In response to the need for safer roads, the city installed a green street along Cully Boulevard in 2011 with planted strips, sidewalks, and separated cycle tracks. [79] The street has become a model for how the city’s transportation and stormwater agencies can work together toward common goals.The city’s continued efforts are being informed by residents who have organized to create better neighborhood infrastructure. In 2012, Verde and its partners launched Living Cully Walks using community-based planning to enhance access to Cully’s open spaces. [80] Neighborhood walks, bike rides, and transit trips were taken to collect local knowledge that informed transit planning and green infrastructure. These events engaged more than 140 participants in the first year, 90 percent of whom were Latinx, to identify significant barriers to safety in moving through the neighborhood. [81] In response, Living Cully and Verde created a neighborhood wayfinding system to safely guide pedestrians and cyclists to local green spaces. The priorities established in this process contributed to the Cully Commercial Corridor and Local Street Plan, adopted by the city council in 2012, which directs neighborhood safety improvements, upgrades to substandard streets, and investments in sustainable transportation. [82] Herrington believes that this model should guide neighborhood change. He said, “The people who are facing the issues at hand should be the leaders in devising the solutions and taking action to achieve those solutions.” [83] Verde’s efforts have focused on how improvements to the neighborhood can also lead to economic opportunities for the community’s residents. Moreno was hired by Verde in 2009 to grow Verde Landscape, a social enterprise venture that provides green infrastructure job training and living-wage employment. [84] He is especially proud of Verde Landscape’s work to transform a 25-acre former landfill into Cully Park. [85]

Its work there started in 2016 with the installation of a community-led green street on 72nd Avenue, providing access to the park. [86] Formerly an unpaved street with no sidewalks or stormwater infrastructure, the avenue now has wide sidewalks and parking areas made with pervious pavers and a safer, narrower driving lane. Rain gardens and bioswales planted with native trees and grasses make the street lush. The project piloted nonstandard designs and trained workers and contractors in building this infrastructure. In the park, Verde Landscape created a habitat restoration area, community garden, and play space. [87] Moreno sees the park as a major success. He said, “The project opened up an opportunity to employ a lot of people from the community and pay them living wages. It has been amazing to watch.” [88] Cully Park opened in June 2018. Today, it is one of Portland’s largest city parks and provides an essential open space to neighborhood residents. [89] In 2009, Verde Landscape was commissioned by the city to install and maintain rain gardens and bioswales, restore habitat, plant trees, and construct parks throughout Portland. It provided approximately sixteen direct jobs, and twenty-three total, for every $1 million worth of contracted services, gradually offering higher-skilled jobs to ensure better wages for employees. [90] Moreno said, “Our crews came from the community. They were able to get trained on these public projects, but eventually they got to work everywhere in the city.” [91] Verde Landscape is a model for neighborhood investment. Unfortunately, due to challenges related to the pandemic, it had to make a difficult decision to close indefinitely. In her book, Resilience for All: Striving for Equity through Community-Driven Design, Barbara Brown Wilson wrote extensively about Living Cully and explained how green infrastructure, active transportation installations, and job-training programs were paired with housing improvements. [92] In summarizing the project’s many successes, she said, “Many green infrastructure project teams flounder when trying to couple social justice with their environmental goals, but in Cully green infrastructure provision is linked explicitly with wealth building and anti-displacement goals.” [93] Portland aims to continue supporting projects like Living Cully. Citywide measures include the grassroots-led Portland Clean Energy Fund, a climate justice fund passed by voters in 2018, which will distribute $50 million a year to invest in projects that support tree planting and rain gardens alongside green jobs and healthy homes initiatives in communities that are underserved. [94] As a result, Living Cully is poised to be just one example of Portland’s progress toward uniting its stormwater goals with the vision of bringing a better quality of life to all its residents.

Notes

“2005 Portland Watershed Management Plan,” Portland Bureau of Environmental Services, March 2006, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/107808.

16. “Portland, Oregon,” Annual Climate Report 2020, National Weather Service Forecast Office, accessed January 12, 2021, https://w2.weather.gov/climate/index.php?wfo=pqr.

17. Noah Garrison and Karen Hobbs, “Rooftops to Rivers II: Green Strategies for Controlling Stormwater and Combined Sewer Overflows,” Natural Resources Defense Council, October 2013, 84–90.

57. “Working for Clean Rivers from Tabor to the River: Partnerships for Sewer, Stormwater, and Watershed Improvements,” Portland Bureau of Environmental Services, accessed October 26, 2018, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/230066.

58. “Innovative Wet Weather Program,” Portland Bureau of Environmental Services, accessed January 10, 2021, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/35941.

59. “New Seasons Market,” Portland Bureau of Environmental Services, accessed January 10, 2021, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/172797

60. Hauth, “Go Natural, Stormwater Solutions.”

61. Burlin, conversation, June 25, 2017.

62. For more information about the Private Property Retrofit Program and its outcomes, see “Tabor to the River: Private Property Retrofit Program Final Report Tabor to the River Phase 1,” Portland Bureau of Environmental Services, accessed October 26, 2018, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/bes/article/508748.

63. Burlin, email message, January 5, 2021; Daniel Kapsch (stormwater engineer, Portland Bureau of Environmental Services), email message to the author, January 7, 2021.

64. Burlin, email message, January 5, 2021; Kapsch, email message.

65. “The Neighborhood Network,” City of Portland, accessed January 17, 2021, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/civic

66. Katya Reyna, “Impact Report 2019,” Depave, accessed January 10, 2021, https://depave.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2019-Impact-Report-compressed.pdf.

67. “2020 Impact Report,” Friends of Trees, accessed January 10, 2021, https://e5p3y2s2.stackpathcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Impact-Report-FY2020.pdf.

68. Burlin, conversation, June 25, 2017.

69. Burlin, email message, January 5, 2021.

70. “2035 Comprehensive Plan,” City of Portland, March 2020, https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-08/comp_plan_intro.pdf.

71. Jena Hughes, “Historical Context of Racist Planning,” Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, September 2019, https://www.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-12/portlandracistplanninghistoryreport.pdf.

72. Burlin conversation, March 26, 2021.

73. Burlin conversation February 2, 2021.

74. BES and the city’s transportation department began this work as part of a cross-bureau green streets program in 2008. Burlin, conversation, February 2, 2021.

75. “Race and Ethnicity in Cully, Portland, Oregon,” Statistical Atlas, accessed February 3, 2021, https://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Oregon/Portland/Cully/Race-and-Ethnicity; “2035 Comprehensive Plan,” I-24.

76. “About Living Cully,” Living Cully, accessed February 3, 2021, https://www.livingcully.org/about-living-cully/; Barbara B. Wilson, Resilience for All: Striving for Equity through Community-Driven Design (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2018), 142–43.

77. Cameron Herrington (program manager, Living Cully), email message to the author, April 30, 2021.

78. Ricardo Moreno (program manager, Verde Builds), in conversation with the author, March 10, 2021.

79. “Cully Boulevard Green Street Project,” Portland Bureau of Transportation, accessed February 3, 2021, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/370405.

80. For a thorough description of this community-based planning effort, see Barbara B. Wilson, Resilience for All, 154–55.

81. “Health and Environment” Living Cully, accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.livingcully.org/programs/health-andenvironment.

82. “Cully Commercial Corridor and Local Street Plan,” City of Portland Bureau of Transportation, accessed May 10, 2021, https://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/520795,9.

83. Herrington, email.

84. For more about Verde’s job program, see Noah Enelow and Taylor Hesselgrave, “Verde and Living Cully: A Venture in Placemaking,” Ecotrust, February 2, 2015, https://www.livingcully.org/incoming/2015/10/NE_Final_PDF_new-Ecotrust-final.pdf, 10; Moreno, conversation.

85. After the land was acquired in 2000 by the Portland Recreation and Parks Department, Verde launched a campaign called ¡Let Us Build Cully Park!, creating a public-private partnership to develop the park and initiating a community-based process for designing it. Together, Verde and Portland Parks and Recreation raised $13 million. “Our Story,” Let Us Build Cully Park, accessed May 14, 2021, https://letusbuildcullypark.org/our-story/.

86. “NE 72nd Greenstreet,” Let Us Build Cully Park, accessed May 14, 2021, https://letusbuildcullypark.org/park-feature/ne-72nd-greenstreet/.

87. “Park Features,” Let Us Build Cully Park, accessed April 22, 2021, https://letusbuildcullypark.org/park-features/.

88. Moreno, conversation.

89. “Cully Park Grand Opening,” Portland.gov, accessed May 14, 2021, https://www.portland.gov/parks/news/2018/6/21/cully-park-grand-opening-saturday-june-30-2018.

90. Noah Enelow et al., “Jobs and Equity in the Urban Forest,” Ecotrust, 2017, https://ecotrust.org/wp-content/uploads/Jobs-and-Equity-in-the-Urban-Forest_final-report_3_8_17.pdf, 68–69; Noah Enelow, email message to the author, May 10, 2021.

91. Moreno, conversation.

92. Wilson, Resilience for All, 141–63.

93. Wilson, Resilience for All, 141–42.

94. “The Story of the Portland Clean Energy Fund,” Portland Clean Energy Fund, July 20, 2020, https://portlandcleanenergyfund.org/campaign-report-toolkit.

Resources

Island Press books: https://islandpress.org/books/ground

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Expand Your Palette: Waterwise Plants for your Landscape

There’s nothing more thrilling to plant lovers than discovering new plants to test in the garden. Here in the southernmost corner of California, we have

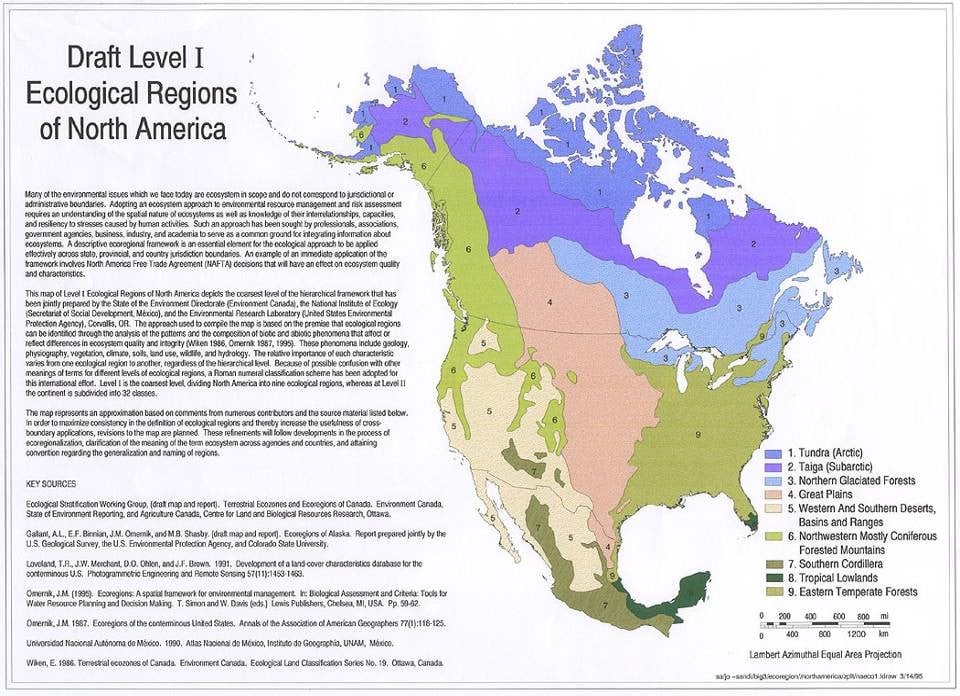

What Climate is This? Part Two – A Garden Futurist Special

Winter 2022 Listen to the Part 2 Podcast here. If you live in the Pacific region, you know that seasons in your garden look different

Nature Therapy from the Contemplative Garden

Winter 2022 Women’s hushed morning voices mingled with crashing waves and chattering crows. “The kettle’s still hot.” “Can you pass the honey?” Whoosh, crash, caw,

Responses