Gardens and Art

Contributor

- Topics: Inspired Gardens and Design

To fill that space with objects of beauty, to delight the eye after it has been struck, to fix the attention where it has been caught, to prolong astonishment into admiration, are purposes not unworthy of the greatest designs.

Humphry Repton, Sketches and Hints on Landscape Gardening (1795)

If we are to learn anything from the great gardens of the past, it is that the garden itself is the work of art. It is not just a setting for “garden art.” Art in the garden is not the statue. It is the organizing ideas that create relationships that, in turn, make the whole much more exciting than the individual tree or sculpture. What the historically great garden cultures have in common is the manner in which they created spaces and views by using all the visual elements: stone walls and hedges; walks paved with gravel, stone, or brick, or simply turfed; buildings, including the main structure, pavilions and follies, gazebos and belvederes, greenhouses and out-buildings; fountains, waterfalls, and pools; and urns and sculptures. The great gardens were created by artists—with or without the help of horticultural experts—and they have a sense of order; they are unified by the design of the entire space—what designers call “good bones.” Some European gardens actually look better in the middle of the winter when the “bones” show, when trees are bare and dark, when there are no flowers, and the snow softens all shapes. Order is achieved through the creative use of not just plants, but the whole visual language of the garden.

Historic Antecedents

Each time and place has its own garden style, its own way of organizing the parts of a garden into a successful whole that reflects some important characteristic(s) of the culture.

Persian gardens were peaceful resting places in a hot climate, with a geometrically shaped pool in the center of four square gardens filled with shade trees, flowers, and fruit. The garden was conceived as an oasis in the hot, barren desert; water, that precious rarity in the desert, was always the central feature. At its most austere, it might be no more than a small fountain in a stone basin in the middle of a square room with stone floors and ceramic tile walls. The tinkling of a small jet of water was sufficient to make the place cool and tranquil. Ancient Greeks and Romans followed many of these same principles in developing their own private gardens.

Italian Renaissance gardens were often located on hillsides and incorporated views to the surrounding countryside. As seen in Villa Lante, more space was given to walks, fountains, pools, sculptures, and stonework than to plants; the latter were usually limited to only a few species, mostly tall trees for shade and hedges clipped into elaborate patterns. Great attention was given to a clear sense of order, symmetry, and flowing sensuality, with interior views focused on a sculpture or a large stone urn.

The French formal gardens, such as those at Versailles, projected the power and control of the kings and noblemen by their large scale, with long vistas, a simple palette of plants, rows of great trees, large reflecting pools, and huge sculptural fountains. These gardens were grand public spectacles, as befit the grandeur of the times.

The English borrowed the concept of the formal garden from the French, but scaled it down to fit their less imperial social and political world, and the smaller scale of the English landscape. In the nineteenth century, there was a continuous and heated debate between the advocates of the formal “Italianate” garden and the proponents of the “natural” landscape garden. In the twentieth century, their love of gardening found full expression in carefully planted garden “rooms”, like those at Sissinghurst and Hidcote.

In Scotland, a land of unlimited gray stone, old castles have an enclosed garden, a rectangular space within tall stone walls. The creators of such gardens often contrasted the solid gray masses with perfectly horizontal planes of immaculately kept lawns. The simple use of stone and grass provided a calm frame for an exuberant display of colors and textures in flower borders. These borders offered unlimited opportunities for individual creative expression.

In America, early gardens such as those at Colonial Williamsburg were designed according to the principles of French gardens with large, simple, symmetrical spaces laid out within perfectly clipped hedges, accented by a repetition of shapes in sheared trees and shrubs.

The Chinese garden was frequently located in the middle of a city where it provided a serene, natural relief from the densely populated neighborhood; it was surrounded by tall walls, pierced at intervals by round “moon gates.” The Chinese valued highly the sculptural presence of large, grotesquely shaped and eroded stones, carefully placed within the garden; these served as elements of mystery, contrasting with the simple planes of the walls. Artificial lakes were a central feature of the larger gardens.

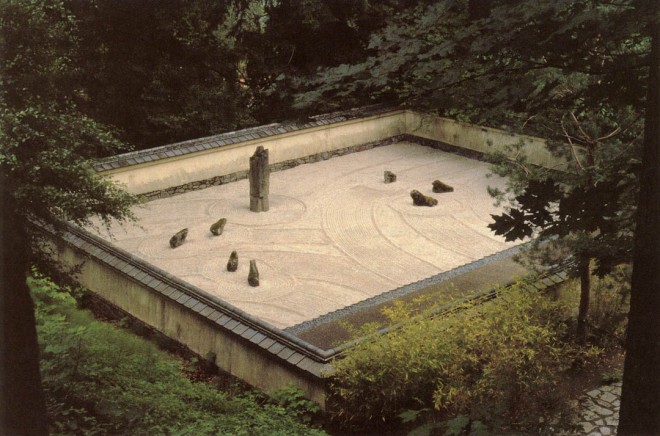

The traditional Japanese garden simulates the experience of wild nature: trees and shrubs of contrasting foliage colors and textures; moss-covered rocks; contorted “windswept” trees; a small stream lined with polished stones; a pond crossed by a footbridge or by stepping stones—all concentrated into a smaller, richer, and more diverse experience than can actually be found in nature. At its extreme, the Zen garden of rocks and sand shows us that we can have an elegant, expressive garden without any plants at all.

Contemporary Approaches

Contemporary artists are finding new ways to create gardens that successfully reflect or draw upon design ideas from the past without directly copying them. In his own Brazilian garden, the late Roberto Burle Marx, a modern master of garden design, created his expression of the classic delineation of space with a stone wall. However, the stone wall has a distinctly twentieth-century abstract, free-flowing character, and provides a beautiful setting for his novel use of tropical, epiphytic bromeliads.

An example of the scale and simplicity of the formal French gardens can be seen at Opus One, a new winery in Napa Valley north of San Francisco. Here the building emerges from the center of a perfectly shaped, grass covered conical mound, with the entrance a “pie slice” cut into the mound. Stone walls, trees, and all other elements are subordinated to the strong image of the green cone.

Another contemporary example is the pool at the Oceanside Civic Center in San Diego County, inspired by the Moorish gardens in Spain and North Africa with their reflecting pools and geometric plantings of date palms and orange trees. Here in Oceanside, the palms, in a perfectly regular grid, are planted in the pool, each one rising out of the water on a small square island.

If we desire the garden to be a visual experience, it should satisfy the same demands we make of other works of art. A sense of order will make us feel that, whatever the style of the garden, everything is in the right place. We should feel that we are seeing something new: an artist’s vision, maybe an unexpected combination of colors and textures; the harmony of a line of trees or statues; a topiary that is not simply another cute chicken, but a large green form unlike any we have ever seen; a path directing our view to a perfectly placed and framed fountain.

The general principles behind the world’s great gardens—especially the importance of order and the definition of spaces—apply equally to a small neighborhood garden. The scale of the garden, or a defined space within the garden, allows for a size and complexity of the plantings and other elements. It is important to understand the significance of scale. For example, an alpine rock garden with its small, ground-hugging plants invites close inspection; viewed from fifty feet away, it is no more interesting than a lawn. On the other hand, a walk lined with twenty tall palms can make a powerful statement, even from a considerable distance.

Our Garden

Our garden in north San Diego County is on a typical suburban subdivision lot of less than a third of an acre. In order to create privacy, our first priority was to screen out views of the neighbors’ homes by planting curtains of bamboo, giant bird-of-paradise, and large philodendrons, along with vines to cover the fences.

Even a small garden can be complex and rich in detail by creating separate areas, or “rooms,” each with its own character. In our garden we’ve given names to about nine different rooms. Each has its own special feeling, and each is clearly defined and separated from its neighbor by painted stucco walls, by distinct changes in level, or by paths paved with rocks collected on our camping trips to the mountains, deserts, and beaches. Some are strongly architectural (The Columns), while others are purely sculptural (The Pyramids), and still others are dominated by plants (the Cactus Garden and the Bromeliad Garden).

“Plop Art” is a derogatory term applied to sculpture that has been stuck somewhere, in a garden or near a building, merely to fill a void, but without establishing any relationship to its surroundings. Any work of art introduced into a garden should look as if the setting was always meant for that piece of sculpture. The art should help to define the space, act as a focal point, or serve some practical function like a gate or an urn that features a special plant.

The most important step in creating a garden—more important than the selection of particular plants—is the definition of space. It brings order to the plant groupings. It frames the views and leads the visitor from one plant to the next. It is the creative organization that characterizes all great gardens. The lines defining a space can be as simple as a row of three small trees, or as elaborate and structured as a clipped hedge, a path, or a stone wall.

After traveling in Italy, I returned home inspired to create my own classical “ruin.” The result was The Columns, a row of four white classical columns that establishes a vertical plane to separate what is in front of the columns (foreground) from what is behind (background), thus clarifying space and distance. To reinforce the order established by the columns, we planted a row of large, succulent agaves (Agave attenuata) behind them, echoing the rhythm of the columns.

Unlike a sculpture, which is usually static and permanent, a garden is a dynamic work of art, constantly changing. Some plants may die while others grow too big for their site. Sometimes we see a new plant that we cannot resist and must make room for in the garden. The well-designed garden can allow for these changes because the basic structure—the definition of spaces—maintains the sense of order that gives the garden its unique character in the first place.

Seasonal changes can bring welcome effects, creating variations on a theme. A sculpture such as the row of white columns, or the white figure on a black pedestal, fixes the framework. It provides the familiar order around which seasonally changing flowers—here, the tall purple grass, the annual growth of a succulent senecio, spring’s mass of yellow oxalis, the giant fantasy foxtails of the agaves—all create different moods for the image we thought we knew.

Merging Plants and Sculpture

One of my great interests as an artist has been to integrate plants with my sculptural forms. I strive to combine the two into a single work of art, so that the viewer will see the plants as sculptural elements, with characteristics of shape, mass, texture, and color that can be appreciated like the elements of a traditional sculpture. The Pyramids is one such sculpture, with the strong, simple forms of the ceramic pyramids alternating with the thick, massive leaves of gasterias (Gasteria spp.) against a background of uniformly gray, polished river rocks. It is a visual play of contrasting colors and textures within a clearly defined geometric relationship.

Some plants look good en masse. Others are distinctive as single specimen plants, each a complete statement; these plants look best when spaced apart and seen against a neutral backdrop or ground cover. Our Bromeliad Garden contains large, specimen bromeliads of many colors and textures: horizontal bands, vertical bands, color gradations, spots and stripes, with colors ranging from green to purple to bright red. If planted close together they would present a confusing mix of colors and patterns. To highlight such spectacular bromeliads in our garden, the individual plants (or clumps of the same species) are separated by an evenly textured and colored ground cover. Rather than use fir bark or pebbles, I made brick-colored, dome-shaped terra cotta “rocks.” These introduce an element of surprise by their unusual size in relation to the plants, yet they unify the Bromeliad Garden as a single concept.

Water is an exciting element in a garden and appears in most great gardens in the form of lakes, small pools, streams, waterfalls, and fountains. A water garden with waterlilies, iris, taro, and other water plants, as well as goldfish and frogs, has a greater concentration of natural life than any similarly sized space in the garden. The Pool by our patio, close to the house, is raised so that we can lean on the wall and enjoy an intimate view of the water just inches below. The three-foot-high walls help define the patio and provided a prominent surface to decorate with my ceramic tiles.

Common Problems, Sculptural Solutions

For every problem there is a conventional solution, perhaps involving some store-bought gadget, but the result will always be the expected, without any surprise. When I encounter a challenge, I try to create my own solution. Supporting The Patio trellis are two carved columns from Michoacan, Mexico, and several others that I shaped on a band saw, for the sake of harmony, rather than resort to simple four-by-four posts. I made the front gate with openings that allow our golden retriever to entertain herself by watching the passing parade of people and cars. Our unique gate is a signal to visitors that they are entering a special place; the enclosed front patio becomes a private entrance hall for our home.

It is possible to introduce a whimsical sculpture into a garden as long as it does not dominate the view or reduce the entire garden to a joke. To protect the plants along our garden paths, particularly in the Cactus Garden, I made a number of hose guards in the form of small clay heads set on short steel posts along the paths. By making them into small sculptures, the hose guards become more than merely utilitarian.

Containers

Urns and other containers have been important elements in gardens for centuries, ranging from large, carved stone urns flanking a palace’s main gate to big ceramic pots planted with citrus that can be brought inside each winter for protection. Containers can help define a space, or they can call attention to a special plant by elevating or framing it. I like to make my own sculptural containers, tailored for specific plants, to create an interesting relationship. An example is the container in the shape of a stool topped with a mound of tiny bromeliads (Abromeitiella brevifolia) simulating a soft pillow. By the front door, the white column with the whimsical red inflorescence of a bromeliad completes the portrait of my wife, Irina.

Art can be a significant factor in creating a garden. If you wish to introduce works of art into your garden, placement is more important than style. This leaves creative room for individual tastes, but each piece will only be successful in the garden if it supports the overall unifying design.

For plant-lovers like us, creating and maintaining a garden always involves a precarious balance between the desire to grow one of everything, and the wish to keep the garden simple and ordered so that the overall design is not lost. I consider our attempts at establishing that balance successful if our visitors leave talking not about how attractive this or that plant was, but talking about the compositions, about the relationship of colors and forms, or about a particularly exciting visual moment that they enjoyed in our garden.

Responses