Party with Trees

Contributor

- Topics: Growing for Biodiversity

Act I: The seed

It was serendipity. I bought Trees of Stanford by Ron Bracewell from a used bookstore to educate myself about the trees on the sprawling Stanford University campus. The book was a quirky labor of love with abstruse information, carefully annotated maps of Stanford, and mysterious codes—“QUag” designating the location of a particular tree. It brought back memories of Our Trees, the book that my parents bought to help us recognize the trees in the little towns in India where I grew up. It made me wonder if I could ever persuade my teenage daughter to carry around a heavy book as a tree guide. Probably not. Indeed, she would likely thumb her way to a tree app if she would ever get her nose out of her smart phone long enough to look at the flora!

That’s when I started to wonder if I could design a course that encouraged freshmen to recognize the beauty and wealth of trees on campus? Could I meld my curiosity about the trees and rejuvenate my rusty background in botany to help create a resource for the community? From that little seed grew the course I jauntily christened “Party with Trees.” I had seen T-shirts emblazoned with that phrase; I wasn’t sure what it meant, but it seemed appropriate. Later I was warned my class title might be interpreted as false advertising, but I don’t agree!

Act II: The seed germinates

So began the journey toward assembling my resources for teaching. Two people, Cindy Weber and John Rawlings, in particular, were instrumental in getting me started. Both were founts of knowledge and offered their unstinting support that allowed me to make the next steps. Cindy, who runs a class at Jasper Ridge for students interested in ecology, rattled off a list of names of other tree enthusiasts. John, a former Stanford librarian, was quieter but vastly knowledgeable about trees and resources on campus. John introduced me to Sairus Patel who keeps up the marvelous Trees of Stanford website. Despite his day job, Sairus quickly became an integral part of the course.

Soon I was meeting with a host of people. For instance, I learned from Julie Cain that Leland Stanford dreamed of making the University a center for agricultural research and wanted it to be the world’s largest repository of plants and trees; today only traces remain of this legacy. Each person mentioned other experts on campus and like a tree grows branches, my network grew. I found numerous people with a deep passion for preserving knowledge, all of whom were ready to teach. Even family and colleagues from around the world contributed photographs, poems, and information!

Act III: The tree grows roots

Now the little plant/course was rooted firmly in Stanford soil and with the help of several well-wishers was beginning to look like it could make it on its own. An enthusiastic graduate student, Kelly McManus signed on as teaching assistant—aka chief gardener! We planned weekly walks twinned with relevant lectures that ranged from learning to use online tools to recognize trees, to appreciating the rich history of the oak plantings on campus, to the usefulness of phylogenetic analyses of trees, to name a few.

Act IV: The tree flowers…

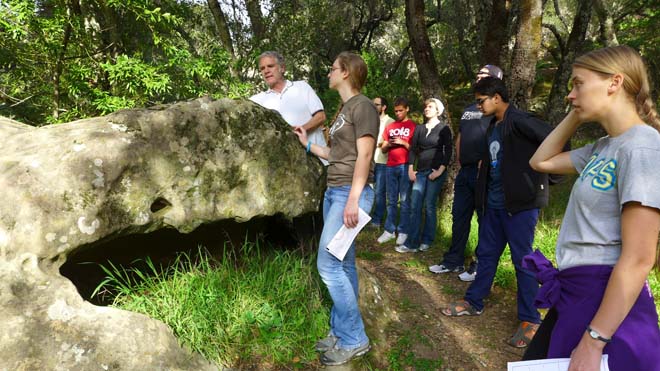

We quickly realized there wasn’t enough time to cover all the aspects of trees we had planned and we pruned our plans. During our first two walks around campus John and Sairus patiently and expertly showed students how one can begin to identify trees. Later, we went on docent-led walks to Jasper Ridge where the students stood dwarfed by the magnificent beauty of redwoods among the remnants of Indian villages and had the chance to practice their tree recognition skills. We even went on a trip to the amazing neotropical rainforest maintained at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS) in San Francisco; I will never forget the wonder on the student’s faces and the fact that not one of them retreated into smart phone-ville while we were on these walks. It really was a party with trees!

And so it was that we walked and talked our way through ten weeks of classes. Sometimes, I brought a snack to each class that matched the theme of the class: kumquats when we talked about edible fruits and so on. Every class had its own unexpected moments. For instance, our planned walk with sustainable farm educator Patrick Archie to the “Be Well” gardens to examine the replanted cherry trees was halted when Air Force One, President Obama’s plane, descended on the field next door! Or when one student remarked during the CAS trip that if he became a billionaire he would build a tropical jungle exhibit for students in India!

Act V: …and fruits

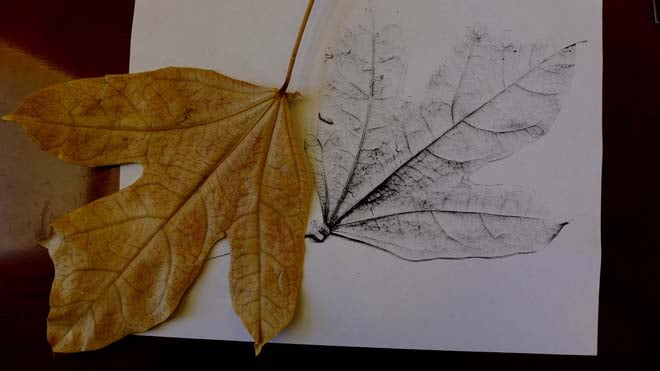

For our class finale the students organized walks incorporating the tools and knowledge they had acquired. They generated Google maps of the route, complete with anecdotes and details about the trees. It was wonderful to witness the ease with which they used the tools at hand to build resources that anyone could access. In addition, students carried out an independent research project of their choice. I was astounded by the diversity and professionalism of these projects. Here is but a snapshot: a reading explaining the marvelous tree-inspired poems of poet laureate and environmentalist Robert Haas; a project interviewing students and faculty members to elicit their opinion on Stanford water policies; an intricate board-game designed to introduce the importance of trees to young children; a research project about tree health and moisture; and even how to construct algorithms to identify leaf shape! And that is only a small sampling of the creativity, I really could not have expected more from a freshman seminar.

In retrospect, our Party with Trees was a success partly because Stanford has an embarrassment of riches and resources that we drew on. But what of the myriad places where students have many fewer opportunities? The preservation of our forests and the environment are global issues, but perhaps the first step is to recognize the importance and silent beauty of trees in our own backyards. Although it started with serendipity, I hope we planted several seeds of curiosity in young minds that will grow and blossom in unexpected ways. After all, to echo Emerson “The wonder is that we can see these trees and not wonder more.”

Further resources:

A Californian’s Guide to the Trees Among Us, Matt Ritter, Heyday, 2011

Our Trees, R.P.N Sinha, Publications Division, Govt. of India, 1968, (out of print)

Trees of Stanford and Environs, R.N. Bracewell, Stanford Historical Society (out of print)

City Tree app, Matt Ritter, iTunes store

Canopy, www.canopy.org

iNaturalist, www.iNaturalist.org

Trees of Stanford, https://trees.stanford.edu

And for more information about the course visit: BIO29N: Party with Trees

Responses