The Days of Compost and Conservation

Contributor

As part of our continuing celebration of silver, honoring twenty-five years of Pacific Horticulture, our editor emeritus concludes his series on the origins of the magazine and its contribution to Western horticulture.

At the Pacific Horticultural Foundation board meeting in February 1975 some members felt that more should be done to find additional readers for the California Horticultural Journal. Most agreed that its content deserved a wider audience, but the Foundation lacked funds to advertise it. This provoked discussion on the journal’s format and it was agreed that something more attractive was needed before promotion was attempted.

The president, Richard Hildreth, then director of the Saratoga Horticultural Foundation, invited board members with an interest in a new format to remain for further discussion after the adjournment. He then charged this ad hoc format committee, not with reporting on the matter to the board, but with producing the journal in a revised format twelve months hence. His strategy neatly circumvented delays that might have been caused by those emphasizing financial risk in the enterprise, while drawing upon the heightened energy and enthusiasm inevitable among those planning the imminent appearance of a magazine, rather than merely a report on one.

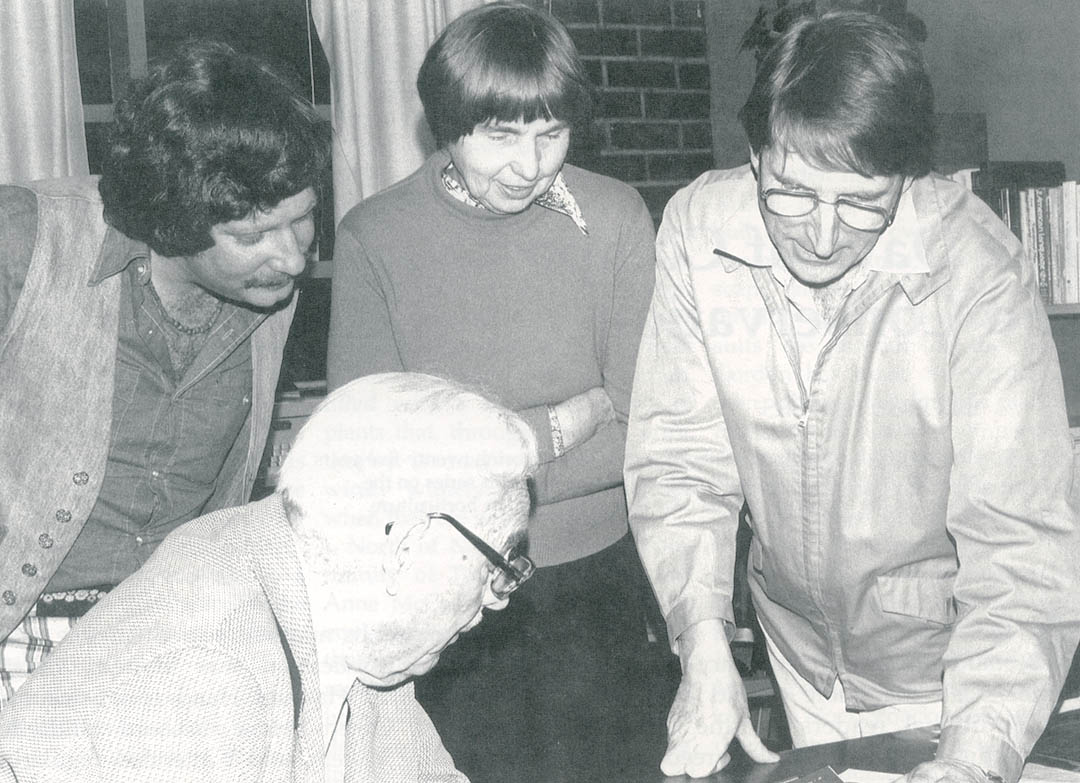

As the format committee confronted questions of publication beyond the shape, size, and typeface to be used, such as distribution, promotion and finance, it became known more formally as the Journal Revision Committee. But it always met informally—and often—in members’ homes. Its numbers varied; anyone with ideas on publication was invited. Marge Hayakawa or Harland Hand conducted the meetings; Owen Pearce, Richard Hildreth, Olive Rice Waters, and I attended regularly. Emily Brown, Elizabeth McClintock, Helen Markwet, and Charles Burr joined from time to time, and Fredrick Boutin and Elizabeth Marshall came up from Los Angeles as often as they were able.

Difficult to compile, but necessary for the Foundation’s minutes book, was a budget for the first year’s operation. The matter was discussed at several meetings but little progress could be made by a committee of gardeners and readers with little financial acumen. At the last moment, Harland Hand produced a document that revealed him as an imaginative balancer of columns and juggler of numbers. The plausibility of his figures enabled the California Horticultural Society and the Southern California Horticultural Institute (now Society) to provide loans of $5,000 each, and the Western Horticultural Society, with a smaller membership, $2,500. This advance enabled the committee to go ahead. Several years later all three societies canceled the loan agreement, feeling that their money had been well used on behalf of their educational aims and obligations and that the Foundation would be harmed by demands for repayment.

Unveiling Pacific Horticulture

The revised journal appeared on time, in January 1976, as Pacific Horticulture, with larger pages than its predecessor, the Journal, more of them, and several with illustrations in color. To ensure good color reproduction a heavy white, clay coated paper was specified, but one that avoided the shiny surface that distracts readers with highlight reflections between the lines of type. A paper called Litho Dull was chosen: Litho referring to the offset litho printing process, Dull denoting the paper’s matte surface.

Initially, color printing was regarded by committee members as too expensive to be contemplated, but gradually opinion shifted. Eventually, despite the additional production cost, it was felt that a publication in which plants were to be seriously discussed and illustrated could no longer expect to flourish with monochrome illustrations alone. The minimum practical number of color pages was eight—one full side of a printed sheet that folded into the magazine as a sixteen-page signature. Of course, the cover needed a color picture in addition to those inside, and that, in a sixty-four page quarterly, remained the pattern for Pacific Horticulture from its inception until about the mid-eighties, when increasing income from circulation combined with donations from readers, allowed for more pages and more color.

Other innovations for the new magazine included the generous use of “white space,” particularly on title pages, and the adoption of Palatino type, an elegant and clear face, light enough to sit appropriately in a magazine but strong enough to make a distinct pattern on the page. The italic version of Palatino is also used for the logotype. Later, an exception was made to the uniform use of Palatino when Bob Raabe’s Laboratory Report began its long and popular life. To set its regular single-page of science notes apart from other contributions, a sans serif type called Helvetica was chosen.

Many of these decisions were made with the help of Laurence Hyman, a designer with experience in both periodicals and technical books. He attended several committee meetings towards the end of 1975, found a local printer able to work within our stringent budget, and took on design and layout of the magazine. His meticulous standards and restrained style suited our conception of the new publication perfectly.

On the cover of the first Pacific Horticulture, the issue of January 1976, was a suitably symbolic photograph of the California poppy (Eschscholzia californica). Inside Elizabeth McClintock gave us its natural history, and Ralph Gould, hybridizer for an English seed company, told of the many garden forms of the poppy. Walter Knight added a column on its cultivation. With this issue was established a policy of embracing the widest possible range of subjects. In addition to the poppy, it included articles on old-fashioned roses; Mahonia ‘Golden Abundance’; bromeliads; sasanqua camellias; abutilons; Ficus benjamina and other figs; desert gardening; California native plants; a group of small plants described by the author as subjects for connoisseurs; Harland Hand’s concrete garden; composting; and Dutch elm disease.

Once again, severe weather took Western gardening in hand when, in the mid-to-late ’70s, several years of low rainfall led to a shortage of water and restrictions on its use. In greater numbers, gardeners learned the value of plants adapted to dry environments, adopted trickle irrigation systems, and became earnest composters and mulchers. The Fall 1977 issue of Pacific Horticulture, therefore, was devoted to a symposium on the drought: SL Gulmon and HA Mooney of the Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, explained the manner in which plants take up and make use of water; Bob Raabe of the Department of Plant Pathology, University of California, Berkeley, gave practical advice on water conservation in the garden; Owen Pearce, then editor emeritus, described Ruth Bancroft’s remarkable garden of succulent plants in Walnut Creek; Russell Beatty of the Department of Landscape Architecture, University of California, Berkeley, provided a social history of western water use in response to periods of plenty and paucity. The quality of these contributions was such that reprints were requested, and the Foundation was able to obtain grants for their production. The wide distribution of this reprint as a color brochure gave much needed publicity to the new publication. Russell Beatty’s article, The Browning of the Greensward, was also reprinted in several other periodicals and remains, I believe, the most widely read of any piece from Pacific Horticulture.

Promoting our New Magazine

Publicity was the new publication’s great need and finding ways and means for bringing it about was the Board’s preoccupation. Bill Lane, of Sunset magazine had arranged for a fine write‑up on our first issue, and this had immediately doubled circulation from the approximately 2,300 of the old Journal to 5,000 for Pacific Horticulture. The first issue was reprinted to meet the sudden demand, and the consequent delay in fulfilling new subscriptions caused some potential subscribers to suspect us of fraud. At this moment, Olive Rice Waters took over as circulation manager and circumvented litigation by arranging for computer addressing, labeling, and speedy dispatch of all copies. The demand for extra copies also revealed shortcomings in our printer’s presses, and a hurried change was needed. The work was taken on by Suburban Press in Hayward, a friendly and cooperative company that has printed every issue since then.

A circulation of 10,000 seemed a not unreasonable target, and with that in mind we sought ways to achieve it. Board members sat together at tables addressing by hand mailing pieces sent to members of the Daffodil Society, the Begonia Society, and others whose officers gave us their membership lists. Nurserymen were also approached in this way and encouraged to offer the magazine to customers. George Budgen, then proprietor of Berkeley Horticultural Nursery, posed at his counter with a copy of the magazine for a photograph promoting Pacific Horticulture among fellow nurserymen; his establishment retains the record in years of support and in total number of copies sold over the counter.

A program of garden tours was launched in 1978 in order to make the magazine better known, and to add a little income. Susan Smith, then proprietor of San Francisco Travel, helped us with plans for a tour in England that year and with many in other countries later on. Little needed to be done to attract participants; there were few competitors then offering similar tours. In subsequent years, the program offered tours in South Africa, Japan, China, Australia, New Zealand, Greece and Turkey, Brazil, Spain and France. Gardeners and plantspeople now have a wide range of other tours to choose from, and filling seats demands much greater effort that in the 1970s.

Displays of the magazine were erected and staffed at flower shows and conferences. The editor gave innumerable talks to garden clubs up and down the coast; radio and television interviews were arranged; newspaper columnists were courted. With help from Dolores Blalock, of California State University, Chico, a video presentation about Pacific Horticulture was made for use by television stations to help them fulfill their community service obligations while assisting our efforts to become better known. By these means some hundreds were added to our list of subscribers and much time and effort consumed. There were only a few volunteers we could call upon for these activities and they would be exhausted before our 10,000 goal was achieved. It was clear that something reaching many more potential readers and demanding far less labor—a direct mail campaign—was needed.

The Friends

Philanthropic foundations were asked to underwrite our promotion effort, but few of them supported horticulture, and fewer still were interested in publications. But the Stanley Smith Horticultural Trust was in another class altogether; it had rescued Curtis’s Botanical Magazine from oblivion and may even have been set up to do so. Where better to plead Pacific Horticulture’s case? The Trust was then administered by Sir George Taylor from his home in Scotland, and an informal inquiry was addressed to him there. His reply was encouraging and free of the questionnaires and red tape of other foundations. He had seen copies of the magazine and liked it. From an exchange of letters including an explanation of our need and IRS tax status came a check that, with the little we had in hand, covered the cost of our first direct mail promotion.

The financial help generated great excitement among all concerned with the magazine. Promotional material, all designed and written “in house,” was mailed to a list of Parks Seed Company customers on the West Coast. The Parks catalog contained a great selection of unusual plants and this we took as a measure of gardening enthusiasm among its customers. Our faith seemed well placed when subscriptions from the mailing amounted to a four percent response—considered an excellent result by those in the business.

Further support from the Stanley Smith Trust came the following year, and subsequently from the LJ Skaggs and Mary C Skaggs Foundation. Meanwhile, Marge Hayakawa launched the Friends of Pacific Horticulture with an editorial in the Summer 1980 issue and a letter to subscribers inviting them to support the publication with donations in addition to their subscription. (The Foundation is recognized by the Internal Revenue Service as a non-profit organization and gifts to it are deductible from the donor’s taxable income.) The response from readers to that first letter generated a new level of confidence in us all, by making it overwhelmingly clear that Pacific Horticulture was highly regarded by its readers. Support for the Friends campaign increases each year, and, with the annual garden party, we thank our donors for their generous support. The event has enabled the Friends to enjoy convivial visits to many remarkable and otherwise private gardens. Details of the Friends campaign and its supporters are found in each April issue of the magazine, and especially in the editorials of the early 1980s.

As numbers increased, part-time assistants were employed to handle circulation and it became necessary to move them out of the Waters’ basement office into a more spacious place. The Berkeley Coop rented us an office adjoining its store on University Avenue. It had a large display window, and in it we hung a sign showing our logotype, Pacific Horticulture, in gold letters. Some board meetings were held there, and the Friends were invited to an office-warming party. After about five years, the Coop developed new plans for the building and our lease was not renewed. The present office on Shattuck Avenue in Berkeley, was rented instead.

In the early 1980s, editorial help was volunteered by Nora Harlow, whose facility with language and skill in proofing and preparing manuscripts was a great boon. Nora also contributed several excellent articles to the magazine, and her reviews, especially of books on garden and landscape design, were models of lucidity and critical insight. The value of her help was soon recognized and her position as a staff member formalized.

A Few of Our Writers

Fine as their contributions have been, it is not possible to mention by name all who have written for Pacific Horticulture. But I feel sure that those omitted here will gladly acknowledge that Lester Hawkins did more than most to establish the tone and authority of the magazine. Fluently combative, as he was in conversation, his writing could also be humorous. His “medium order of angels” observing for us from above the movement of cloud masses near the equator is an unforgettable lesson in weather changes for western gardeners (Winter ’80). Discussing the classic English herbaceous border, Lester analyzed its structure and components so as to enable readers to picture and, in their minds, enjoy the artistry and craftsmanship in its creation while, at the same time, understanding the absolute necessity for gardening in an entirely different way here in the West (Spring ’84). His series of articles, mainly in issues of the early 1980s, represent the most original and vigorous expression of gardening ideas to be found at that time anywhere in the English language. When Lester died, in 1985, the editor lost, and greatly mourned, not only a good and lively friend, but also the several contributions promised by him, and the energizing evening telephone discussions over manuscript details. Most of his earlier articles are included in the Pacific Horticulture Book of Western Gardening, one purpose of which was to make Lester’s writing more widely available in durable binding.

Elizabeth de Forest, who, with her husband, contributed to Sydney Mitchell’s original California Horticultural Journal, was now a widow, but still active in Santa Barbara. She unearthed a number of hand-tinted photographic lantern plates of the city’s famous old gardens. To these she added a fascinating historical background on the gardens and their makers for the Winter 1977 issue; the lantern plates converted to handsome printed pictures in color.

Hal Bruce, the garden taxonomist at Winterthur, was intrigued to discover the extent to which Henry F DuPont had stocked the garden there with plants from the WB Clarke Nursery, in San Jose, California. He wrote, also in the Winter 1977 issue, discussing some of these plants in hopes of digging up information on others. Bruce’s book, How to Grow Wildflowers and Wild Shrubs and Trees in Your Own Garden (Knopf, 1977), showed him to be a devoted student of nature, a perceptive gardener, and a fine writer. He was also somewhat ahead of the pack. Unfortunately Bruce died while quite young; a great loss to gardening.

Despite the emphasis in Pacific Horticulture on gardening in a mediterranean climate, the magazine has earned the high regard of many gardeners in England. Will Ingwersen, “Cherry” Ingram, and Graham Thomas, all well known to gardeners in that country, have contributed articles, and have told of the reputation the magazine has earned there. No fewer than three times, The Garden, magazine of the Royal Horticultural Society, has endorsed it in laudatory manner, and in The Gardener’s Year Book, another RHS publication, it is described as “the best of publications for gardeners in the US.”

Soil conservation and low water use were, by the 1980s, accepted as essential aspects of thoughtful gardening, but only among a conscientious minority; spreading those ideas more widely has been slow and difficult work. As Russ Beatty explained in The Browning of the Greensward, with the return of normal winter rains after a serious dry period, water-saving measures are quickly forgotten. Joe Williamson, some years later, proposed that we no longer refer to drought in the West because the word suggests an abnormal shortage of water, whereas a shortage is, in fact, the permanent condition.

Difficulties faced by advocates of low-water-use gardens include the deeply embedded European esthetic of green lawns and lush borders, and the continuing paucity of attractive gardens other than those to photograph for publication. Furthermore, even Pacific Horticulture, dedicated as it is to modes of gardening appropriate for the West, would quickly turn its readers away from the idea if every page were given over to water-saving ways and means. The policy has been to be gentle and persistent in its advocacy.

Ideas of soil conservation have benefited from the growth of recycling and conservation as a whole. Nowadays, many more gardeners are composting refuse in their own back yards. Plant debris is collected at curbside and composted in municipal yards for return to the land. Wood waste is composted with sewage and the resulting manure is bagged and sold to landscapers and home gardeners. Despite the progress that these examples represent, in the matter of sewage treatment and proper use we have a long way to go; far too much of it is still discharged into the sea and enormous soil fertility thereby lost.

There is much more that could be said about Pacific Horticulture, its writers, editors, staff and supporters, and, of course, about the art and craft of gardening. Here, however, I must leave matters, fearing that I have already detained the reader too long, but hoping that some, at least, will find the story sufficiently intriguing to pursue for themselves in past issues and in the ever more colorful pages of those to come.

[sidebar]

An Oral History

Those interested in further reading about the art and craft of gardening may wish to read the recently completed oral history of our first editor, W. George Waters: English Garden History, Western Gardening, and Creating and Editing Pacific Horticulture. (2000, Oral History Department, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.). A copy of the book is in the Helen Crocker Library of Horticulture at Strybing Arboretum. Copies may be ordered directly from the Oral History Department by calling 510/642-7395.

[/sidebar]

Responses