The Native Plant Garden in Fall

Contributor

Fall 2021

The floor of the Sacramento Valley is mostly flat agricultural land veined with a network of creeks, sloughs, levees, and dams all constructed to collect and direct winter rainfall. Along such a slough is our one-acre private native garden begun more than 15 years ago by myself, Patricia, and now enjoyed and managed in a wonderful partnership with Pat.

Fall is in the air and this is my favorite season of all. It is a short season of only two months (October and November). The riot of color in the spring is a distant memory and the brown of summer will change to green as the rains return. The weather is still pleasant with some crisp, cool mornings, but it is all of the colors and textures I love the most! Pat’s favorite season depends on the rain. If the first rain is in the fall, she loves when the moisture enhances the colors of the fallen leaves.

This season is the start of new growth. We look forward to the little green tufts of the cool-season grasses and germination of wildflowers such as tufted poppy (Eschschoizia caesitosa). We usually find fungi emerging again and the magic of a frost is almost certain as well.

Seeds, pods, berries…and more

Our native garden in fall is filled with many surprises. Rosehips, berries, and seeds attract the birds. The seed pods are unique and amazing and the fallen ragged leaves develop color and character. We collect many types of seeds and pods in late summer into fall for future seeding, sharing, and to appreciate as decoration.

Fall has so many interesting textures—some of our favorites are captured below. Can you recognise these plants growing in our native garden?

Fall Planting

Fall is the time of looking forward as we put new plants into the ground. Planting in this season allows plants to establish new roots as the rains resume. We always hope for a couple of inches in November, but know we need to be patient since most rain will not fall till winter and early spring.

Probably the most challenging part of planting is figuring out what native plants need and where in our garden we can best meet their needs. Resources are so much better now than when we started our first plantings 15 years ago. I had a rather tall stack of books, each with limited information. I still sometimes look back at the information sheets I started in trying to learn about my first 150 or so species/cultivars. Amazingly we now grow about three times that number.

Truthfully, we are still learning and have had failures and unhappy plants along the way. This exercise to figure out where plants will thrive is not easy and takes a while—it is a bit like a puzzle. It is great when everything works out but when it doesn’t, we regroup and try again. We have been disappointed when, after research and even planting, we have had to declare a desired plant a poor choice for our garden or climate. This is all a process, but a process Pat and I very much enjoy!

For every new plant species, I start with Calflora to discover where our plant grows and in which plant communities. California is so diverse! Once we learned about these plant habitats, we had clues for placement and grouping of plants. Next, to find more information about the species, including where and how it is grown, I check Calscape. It includes much of the information we need all in one place.

And finally, I also check some of my books again and the websites of a few trusted nurseries. Surprisingly, there is always some additional information not found in Calflora or Calscape, although they are very helpful sources. To make things even more interesting, not all of our resources will agree. Are we discouraged? Not at all, this is part of the process.

One frustration, however, is because of all the variation within a species, mature plant size can vary greatly! When designing a garden, this information is necessary for plant placement. We have also observed that our nutrient-rich, wonderful clay soil often grows larger plants than found in the plant descriptions. When this happens and a shrub is growing into the paths, Pat’s solution is to just change the path—which she does often, to my horror as the designer. But now I am getting used to it and agree that constant pruning is not the answer in our wild garden. In a natural setting, paths do change over time.

Establishing Annual Wildflowers—Not Easy

We keep trying to establish more annuals, continuing to increase plant diversity to attract pollinators and support wildlife. But there are so many factors to consider: when to plant, how to ensure good germination and growth, how to keep pests from eating seedlings, and how to control weeds. We also want to increase chances of returning annuals in future years and accommodate garden changes. Over time as the trees and shrubs have matured, the microclimates in our once open areas have evolved and the sun-loving annual wildflowers have decreased. Gardens are always changing as plants grow, mature, burn, or die; the plant composition must change as well. Experimentation continues with new annual species in shadier settings, and we are always trying to figure out what works, what doesn’t, and why.

We read in the literature that many wildflowers prefer to grow in bare soil, but we are not so sure. Our organic mulch reduces weeds, so we are always excited when an annual thrives in deeply mulched areas. Once, while trying to eradicate a weed in the patch of annual red maids (Calandrinia menziesii), we removed the weeds and mulched heavily with woodchips, expecting nothing to grow in that area the next year. Thankfully the weed was reduced, but to our surprise there was no difference at all in the germination of the red maids in the mulched and unmulched areas. This is very useful maintenance information and a reason to find more annual wildflowers that aren’t deterred by a heavy mulching.

Many plants germinate with disturbance, and we have discovered this when seedlings seemed to germinate in paths and not where we wanted or planted them. Now we even encourage visitors to pretend they are elk or deer by walking off the paths to explore, which increases disturbance with more pockets, ruts, moved debris, and scarified seeds. We now understand and pay more attention to “grows in disturbed areas” found in plant descriptions.

Center: Seedlings germinating under a nurse plant in natural debris. Annual meadowfoam (Limnanthes sp.) under clustered field sedge (Carex praegracelis) in our valley grassland swale. Credit: Patricia Carpenter

Right: Chinese houses (Collinsia heterophylla). Credit: Beth Savidge

Besides the cages, sticks, and plant trays we use for pest control, more and more we are using plant debris and nurse plants. The old plant stems—fallen over, stomped, or still upright—seem to shade and protect the new seedlings. Pat looks forward to one of her favorite annuals, Chinese houses (Collinsia heterophylla), that has returned to the same place for over 10 years, with more variation each year. There is now an established seed bank allowing the seedlings to germinate in the naturally formed, not-too-thick mulch. Here they are protected by nurse plants as well. Every year we observe this area to try to figure out why it is so successful, hoping to use this information as we encourage other annual species to return each year. We also frequently find returning annuals sprouting just under the edge of a shrub, and deciduous shrubs are extremely useful in hiding tasty new little annual seedlings from foragers.

I remember when I had my first garden while attending university, I asked my green-thumb father when to plant some seeds he had given me. He said, “Just plant them, and they will come up when it is the proper time.” Although I regularly ignore his advice and try to plant when I think the time is right, I am often discouraged. For survival, native seeds wait for the proper conditions like temperature, moisture, smoke, scarification, and light before germinating—but this could take years. As a consequence, Pat and I have found that regularly neither annual nor perennial seeds germinate at all in the year seeded and now resignedly wait until we are rewarded in a subsequent year. Gardening with natives takes patience.

How do we keep track of all this? Good records and notes—trust us, they will come in handy! I just recently looked up something from a planting in 2006, thank goodness I wrote it down.

Planting Along the Slough

Our slough can fill with winter rains, but is also consistently filled from agriculture runoff during the spring and summer. It starts to dry in the fall. Due to the extreme drought this year, farmers planted fewer crops. This was the first spring/summer in our garden’s 40 years that the slough was completely dry. Very concerning!

The farmers control our water. Depending on what is planted, the slough may have large amounts of water in spring and summer, with each irrigation flooding the banks. In recent years the slough can alternate between completely dry and wet, also cycling with irrigations. The combination of winter rain and farmers’ irrigation means water availability is different every year. Planting along a slough is not like a typical riparian setting. Most riparian plants expect winter floods during cool weather, not summer flooding.

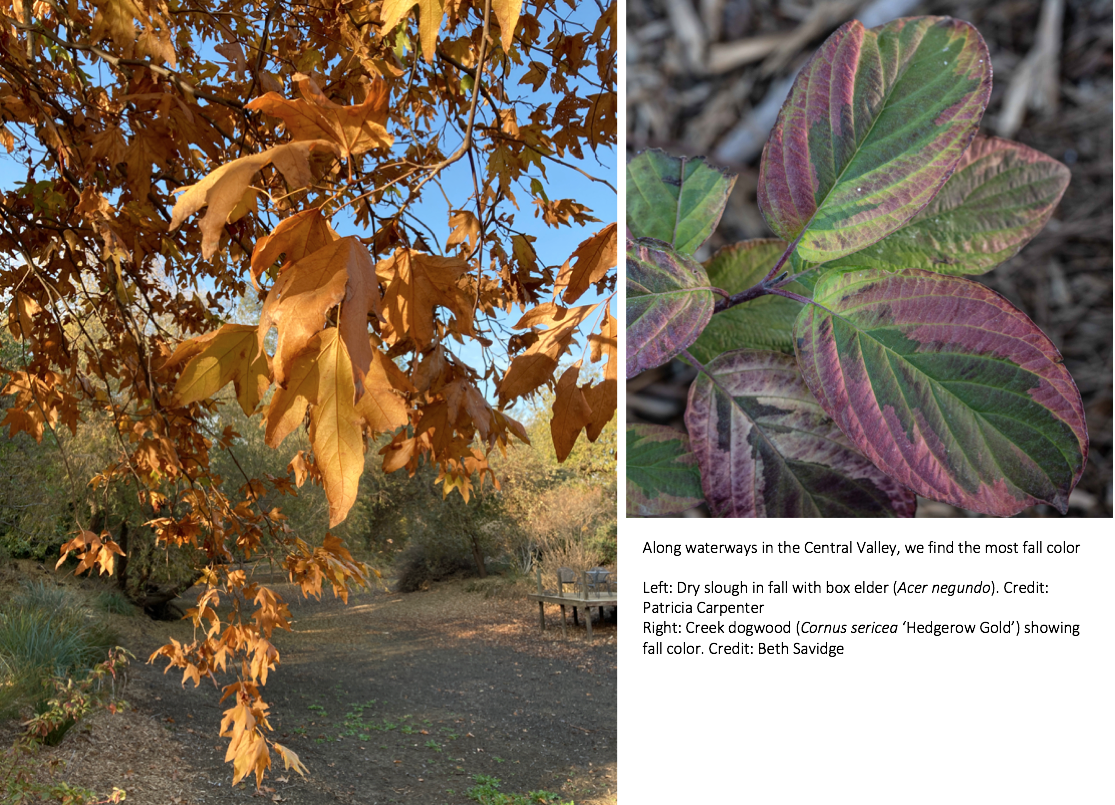

When I started the native garden there were only weeds along the banks of the slough, a couple valley oaks (Quercus lobata), and a Goodding’s black willow (Salis gooddingii). Most of the trees and large shrubs we planted are deciduous and include California sycamores (Platanus racemose), blue elderberry (Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea), buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), buckeye (Aesculus californica), and box elder (Acer negundo). The evergreen bay laurel (Umbellularia californica) grew very slowly at first but is now a wonderful mature tree. The trees and shrubs provide the structure to add many additional plants that stabilize the bank during high water or floods and increase diversity and interest. It took two tries to establish the buttonbush, the first one floated away. It is important to secure and protect the small new plants until the roots can cope with flooding. Although riparian plants love water, most can adapt to drought conditions.

There are numerous species of rushes and sedges, but two of our favorite large herbaceous perennials are found along waterways in our area, blooming in the summer and fall. Hairy-fruited hibiscus (Hibiscus lasiocarpos) has very large white flowers as well as interesting buds and seed pods. It spreads by rhizomes and seed. Leather root (Hoita macrostachya) is a legume with purple flowers. Both have thrived on the edge of the slough for almost 15 years, and we propagate them regularly.

The Five Seasons in our Native Garden

We are back where we started a year ago with the fungi appearing once again as the fall brings cooler weather and winter approaches. We are hopeful that the future allows us to share the wonders of our wild escape on the slough with more visitors. Pat and I are excited to experience the unfolding of the coming year with its five amazing seasons.

Key to fall texture:

- Fall bouquet of iris (Iris ‘Pacific Coast’). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Valley oak (Quercus lobata) leaves. Credit: Beth Savidge

- Flowers and seeds of telegraph weed (Heterotheca grandiflora). Credit: Beth Savidge

- San Diego sedge (Carex spissa) grows along the slough. Credit: Beth Savidge

- Seed pods of the fragrant pitcher sage (Lepechinia fragrans). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Salvia ‘Pozo Blue’ seed stalk. Credit: Beth Savidge

- Red berries of toyon (Heteromeles arbutifolia). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Dangling seed pods of desert willow (Chilopsis linearis). Credit: Beth Savidge

- California poppies (Eschscholzia californica) after petals fall. Credit: Beth Savidge

- Toluaca seeds (Datura wrightii). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Seed pods of doubleclaw (Proboscidea parviflora). Credit: Patricia Carpenter

- Seed pods of Lewis’ flax (Linum lewisii lewisii). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Pods of the dense flowered platycarpos (Lupinus microcarpus densiflorus). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Common selfheal seed pods (Prunella vulgaris). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Seed pods of bristly matilija poppy (Romneya trichocalyx). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Seeds dispersing in Indian milkweed or Kotolo (Asclepias eriocarpa). Credit: Beth Savidge

- Roger’s red grape (Vitis ‘Roger’s Red’). Credit: Patricia Carpenter

- Bark of quailbush (Atriplex lentiformis breweri) exposed after a pruning. Credit: Ona Willoughby

- Husks of the northern California black walnut (Juglans hindsii). Credit: Beth Savidge

Resources

Beth Savidge photos of Patricia’s native and main gardens (2020, 2021)

Share:

Social Media

Garden Futurist Podcast

Most Popular

Videos

Topics

Related Posts

Design Futurist Award Announced: Committee Shares Vision

March 8, 2023 At Pacific Horticulture, we believe that beauty can be defined not only by gorgeous plants and design, but also by how gardens

Expand Your Palette: Waterwise Plants for your Landscape

There’s nothing more thrilling to plant lovers than discovering new plants to test in the garden. Here in the southernmost corner of California, we have

Portland Parks’ “Nature Patches”

Winter 2022 Nature is so beautiful when left to its own devices, yet crisply manicured lawns remain a status symbol. This is true in Portland,

Readily Available Low-Water Plants for a Warming Climate

Fall 2022 Al Shay is the manager of the Oak Creek Center for Urban Horticulture on the campus of Oregon State University (OSU) in Corvallis.

Responses